Codes Of Practice

Developed through NFACC

- Bison

- Dairy Cattle

- Farmed Fox

- Farmed Mink

- Farmed Salmonids

- Goats

- Pullets and Laying Hens

- Rabbits

- Veal Cattle

Under Revision

Archived Recommended Codes of Practice

Code Development Process

Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pullets and Laying Hens

| PDF |

ISBN 978-1-988793-50-4 (book)

ISBN 978-1-988793-51-1 (electronic book text)

Available from:

Egg Farmers of Canada

21 Florence Street, Ottawa, ON K2P 0W6

Telephone: 613-238-2514

Fax: 613-238-1967

Website: www.eggfarmers.ca

Email: cpa@eggs.ca

For information on the Code of Practice development process contact:

National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC)

Website: www.nfacc.ca

Email: nfacc@xplornet.com

Also available in French

© Copyright is jointly held by Egg Farmers of Canada and the National Farm Animal Care Council (2017)

This publication may be reproduced for personal or internal use provided that its source is fully acknowledged. However, multiple copy reproduction of this publication in whole or in part for any purpose (including but not limited to resale or redistribution) requires the kind permission of the National Farm Animal Care Council (see www.nfacc.ca for contact information).

Acknowledgment

|  | |

Funding for this project has been provided through the AgriMarketing Program under Growing Forward 2. Amendments have been made with financial support from the AgriAssurance Program under the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership.

Disclaimer

Information contained in this publication is subject to periodic review in light of changing practices, government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/or without seeking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the authors shall not be held responsible for loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Furthermore, the authors expressly disclaim all and any liability to any person, whether the purchaser of the publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, by any such person in reliance on the contents of this publication.

Cover image (top left and right) courtesy of L.H. Gray & Son Limited

Cover Image (bottom) courtesy of Egg Farmers of Canada

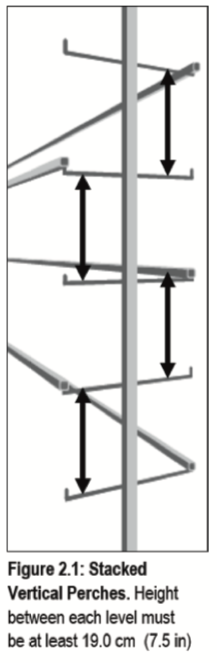

Perching Diagram (p. 25) Illustration by Jeremy Prapavessis

Table of Contents

| Preface | ||||

| Introduction | ||||

| Glossary | ||||

| Section 1 Pullet Housing and Rearing | ||||

| 1.1 | Pullet Housing | |||

| 1.1.1 | Housing Equipment: Design and Construction | |||

| 1.1.2 | Flooring | |||

| 1.1.3 | Feeders and Waterers | |||

| 1.1.4 | Space Allowance | |||

| 1.1.5 | Special Considerations for Multi-Tier Rearing Systems | |||

| 1.1.6 | Perches | |||

| 1.2 | Receiving and Brooding Chicks | |||

| 1.3 | Lighting | |||

| 1.4 | Pullet Rearing and Reducing Fear | |||

| Section 2 Housing Systems for Layers | ||||

| 2.1 | Housing and Equipment: Design and Construction | |||

| 2.2 | Flooring | |||

| 2.3 | Feeders and Waterers | |||

| 2.4 | Enriched Cage and Non-Cage Housing Systems | |||

| 2.5 | Transitioning from Conventional Cages | |||

| 2.5.1 | Space Allowance | |||

| 2.5.2 | Nesting | |||

| 2.5.3 | Perching | |||

| 2.5.4 | Foraging and Dust Bathing | |||

| 2.6 | Special Considerations for Multi-Tier Systems | |||

| 2.7 | Access to Outdoors | |||

| 2.7.1 | Housing and Range: Design and Construction | |||

| 2.7.2 | Range Management | |||

| 2.7.3 | Feeders and Waterers: Access to Outdoors | |||

| Section 3 Barn Environmental Management | ||||

| 3.1 | Ventilation and Air Quality | |||

| 3.2 | Temperature | |||

| 3.3 | Noise | |||

| 3.4 | Lighting | |||

| 3.5 | Litter Management | |||

| Section 4 Feed and Water | ||||

| 4.1 | Feed and Water Management | |||

| 4.2 | Nutrition | |||

| 4.2.1 | Nutrition to Manage Bone Health | |||

| 4.3 | Water | |||

| Section 5 Health Management and Husbandry Practices | ||||

| 5.1 | Pullet Sourcing and Transition to Lay | |||

| 5.2 | Health Management Plan | |||

| 5.3 | Skills Related to Flock Management | |||

| 5.4 | Disease Prevention and Management | |||

| 5.4.1 | Sanitation | |||

| 5.4.2 | Pest Control | |||

| 5.5 | Inspections | |||

| 5.6 | Sick and Injured Birds | |||

| 5.7 | Harmful Behaviour | |||

| 5.7.1 | Feather Pecking and Cannibalism | |||

| 5.7.1.1 On-Farm Beak Trimming | ||||

| 5.7.2 | Panic, Hysteria, and Smothering | |||

| 5.8 | Controlled Moulting | |||

| 5.9 | Emergency Management and Preparedness | |||

| Section 6 Handling and Transportation | ||||

| 6.1 | Pre-Transport Planning | |||

| 6.1.1 | Feed and Water: Pre-Loading | |||

| 6.2 | Fitness for Transport | |||

| 6.3 | Handling and Catching | |||

| 6.4 | Loading and Unloading | |||

| 6.5 | Facilities Design and Maintenance | |||

| Section 7 Euthanasia | ||||

| 7.1 | On-Farm Euthanasia Plans | |||

| 7.2 | Skills and Knowledge | |||

| 7.3 | Decision Making around Euthanasia | |||

| 7.4 | Methods of Euthanasia | |||

| Section 8 On-Farm Depopulation | ||||

| 8.1 | Planned On-Farm Depopulation | |||

| 8.2 | Emergency On-Farm Depopulation | |||

| References | ||||

| Appendices | ||

| Appendix A | - Transitional and Final Housing Requirements for Enriched Cages | |

| Appendix B | - Transitional and Final Housing Requirements for Non-Cage Housing | |

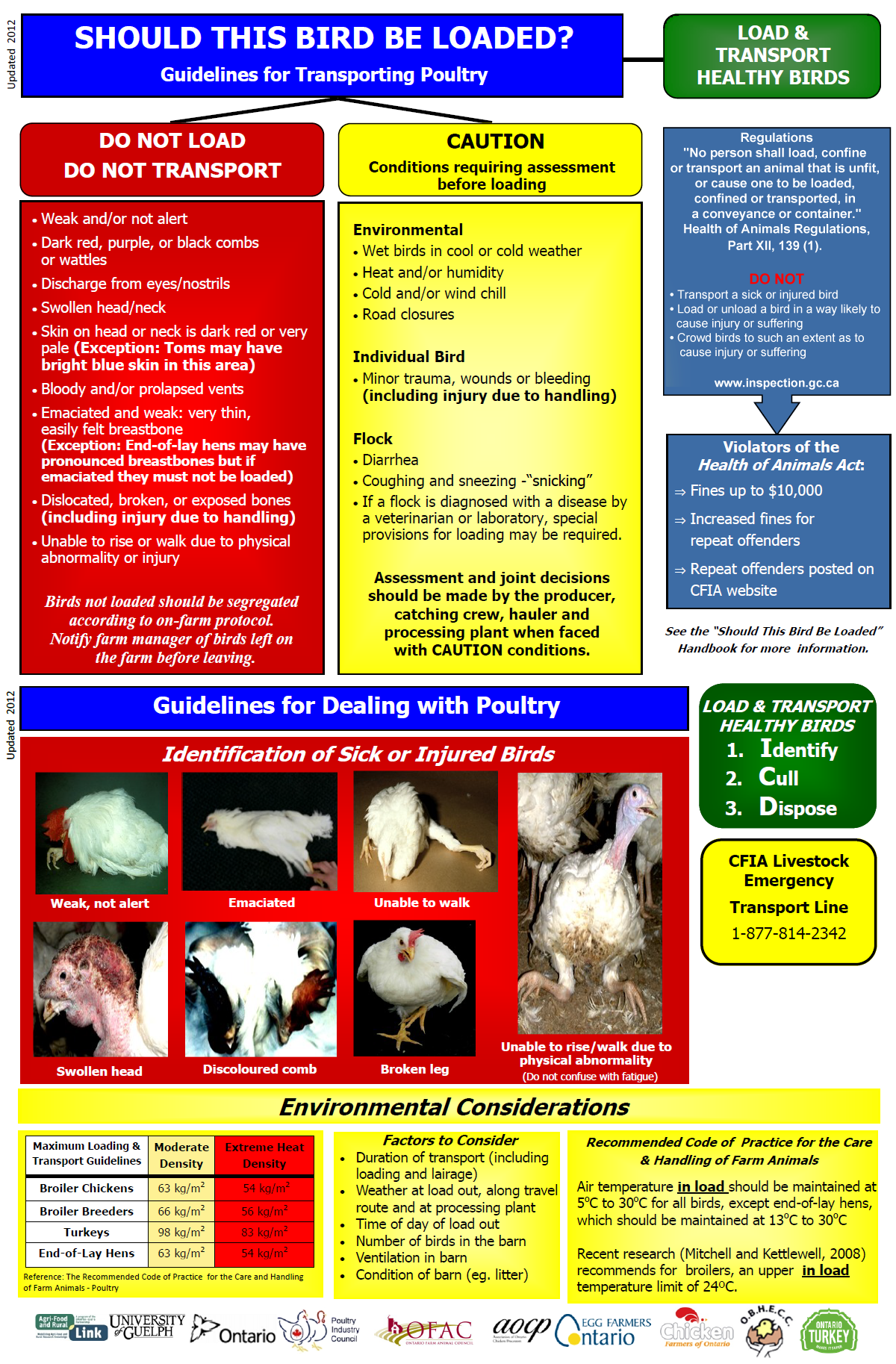

| Appendix C | - Guidelines for Transporting Poultry | |

| Appendix D | - Example Euthanasia Decision Guidance | |

| Appendix E | - Acceptable Methods of Euthanasia | |

| Appendix F | - Resources for Further Information | |

| Appendix G | - Participants | |

| Appendix H | - Summary of Code Requirements | |

Preface

The National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC) Code development process was followed in the development of this Code of Practice. The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pullets and Laying Hens replaces its predecessor developed in 2003 and published by the Canadian Agri-Food Research Council (CARC).

The Codes of Practice are nationally developed guidelines for the care and handling of farm animals. They serve as our national understanding of animal care requirements and recommended practices. Codes promote sound management and welfare practices for housing, care, transportation, and other animal husbandry practices.

Codes of Practice have been developed for virtually all farmed animal species in Canada. NFACC’s website provides access to all currently available Codes (www.nfacc.ca).

The NFACC Code development process aims to:

- link Codes with science

- ensure transparency in the process

- include broad representation from stakeholders

- contribute to improvements in farm animal care

- identify research priorities and encourage work in these priority areas

- write clearly to ensure ease of reading, understanding and implementation

- provide a document that is useful for all stakeholders.

The Codes of Practice are the result of a rigorous Code development process, taking into account the best science available for each species, compiled through an independent peer-reviewed process, along with stakeholder input. The Code Development process also takes into account the practical requirements for each species necessary to promote consistent application across Canada and ensure uptake by stakeholders resulting in beneficial animal outcomes. Given their broad use by numerous parties in Canada today, it is important for all to understand how they are intended to be interpreted.

Requirements - These refer to either a regulatory requirement or an industry imposed expectation outlining acceptable and unacceptable practices and are fundamental obligations relating to the care of animals. Requirements represent a consensus position that these measures, at minimum, are to be implemented by all persons responsible for farm animal care. When included as part of an assessment program, those who fail to implement Requirements may be compelled by industry associations to undertake corrective measures or risk a loss of market options. Requirements also may be enforceable under federal and provincial regulation.

Recommended Practices - Code Recommended Practices may complement a Code’s Requirements, promote producer education, and can encourage adoption of practices for continual improvement in animal welfare outcomes. Recommended Practices are those that are generally expected to enhance animal welfare outcomes, but failure to implement them does not imply that acceptable standards of animal care are not met.

Broad representation and expertise on each Code Development Committee ensures collaborative Code development. Stakeholder commitment is key to ensure quality animal care standards are established and implemented.

This Code represents a consensus amongst diverse stakeholder groups. Consensus results in a decision that everyone agrees advances animal welfare but does not imply unanimous endorsement of every aspect of the Code. Codes play a central role in Canada’s farm animal welfare system as part of a process of continual improvement. As a result, they need to be reviewed and updated regularly. Codes should be reviewed at least every five years following publication and updated at least every ten years.

A key feature of NFACC’s Code development process is the Scientific Committee. It is widely accepted that animal welfare codes, guidelines, standards, or legislation should take advantage of the best available research. A Scientific Committee review of priority animal welfare issues for the species being addressed provided valuable information to the Code Development Committee in developing this Code of Practice.

The Scientific Committee report is peer reviewed and publicly available, enhancing the transparency and credibility of the Code.

The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pullets, Layers, and Spent Fowl: Poultry (Layers): Review of Scientific Research on Priority Issues developed by the Poultry (Layer) Code of Practice Scientific Committee is available on NFACC’s website (www.nfacc.ca).

Introduction

Codes of Practice strive to promote acceptable standards of care for animals in such a way that achieves a workable balance between the welfare needs of animals and the capabilities of farmers. Egg production in Canada involves interaction between pullet growers who rear birds starting with day-old chicks until about 19 weeks of age and egg farmers who care for the hens throughout the laying phase. Canada’s egg industry is committed to prioritizing the health and well-being of all birds entrusted to their care. This commitment forms the basis of the industry’s national Animal Care Program (ACP), first introduced in 2005 and based on the previous “Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pullets, Layers, and Spent Fowl.”

While Codes of Practice for egg layers have been relied on in Canada for more than a decade, this Code, which utilizes NFACC’s science-informed and consensus-based process, establishes firm guidelines to which pullet growers and egg farmers will be held accountable. In addition to advancing welfare requirements in key production areas such as barn environment, health and husbandry practices, transportation, and euthanasia, this Code mandates the phase out of conventional cages, so that hens may have more freedom of movement and the ability to perform a variety of natural behaviours.

This move to phase out conventional cages is a substantial undertaking that represents the most significant change ever to egg production in Canada. Since more space per bird, along with furnishings to accommodate hen behaviours, is required, existing facilities will not be able to accommodate the same number of hens. As a result, new barns will have to be built in order to produce the same number of eggs. This Code includes a transition strategy that allows for housing conversions to be completed on a staggered, practical, and orderly basis. It is expected that 50% of hens in Canada will be transitioned to alternative housing systems (i.e. enriched cages; non-cage housing) within 8 years.

In addition to the physical and structural housing changes that will have to be undertaken, this Code also considers other elements that are important to bird welfare. Alternative housing systems to which hens will be moved present complex welfare trade-offs that are addressed in this Code. For example, significant changes to pullet rearing environments are necessary to support hen welfare in non-cage housing systems in layer barns. In addition, new management practices in layer barns will have to be learned, and additional labour will likely be required to ensure that hen health and welfare needs are met.

Perhaps one of the most significant undertakings of this Code involves the inclusion of specifications for the alternative housing systems to which hens will be transitioned. A great deal of thought and consideration was given to the development of this Code to ensure that the welfare needs of hens are met regardless of the housing system utilized. While increasing space and allowing for more natural behaviour, alternative housing may not result in the desired welfare improvements if the housing is not properly constructed, maintained, and managed. This Code contains robust housing and management standards for alternative housing systems that the Code Development Committee (CDC) believes jurisdictions outside of Canada can also reference.

Finally, the transition strategy that the CDC has developed represents an organized approach that allows the industry to phase out conventional cages in an orderly manner that is practical, feasible, cost-efficient for farmers and consumers, and ensures that the market demand for eggs can continue to be met, while significantly improving the welfare of millions of hens.

This Code is a guideline for the care and handling of pullets and laying hens, and applies to both regulated and unregulated egg production, including backyard flocks. It plays an important role in the industry’s efforts to assess animal care on farms across Canada. This Code does not apply to egg or meat processing, or transportation beyond the farm gate. In addition, it does not apply to breeders or hatcheries; however, it is expected that practices at hatcheries and layer breeder facilities will be included in the next Code revision. This will encompass a review of research on in-ovo sexing, which is regarded as both a welfare and economical benefit. In the meantime, the egg industry continues to support research on in-ovo sexing with the goal of finding a commercially available solution. All applicable provincial and federal acts and regulations continue to take precedence.

Glossary

The following terms and definitions refer only to how the terms are used in this document.

Accessible Feed Space: Amount of available feed trough space, as measured in linear inches, provided to each bird. Depending on the location of the trough, available space can be provided on one side of the trough or on both sides.

All-In/All-Out: A production strategy whereby all birds are moved into and out of facilitites and/or between production phases.

Ammonia: A noxious gas common in animal production that forms during breakdown of nitrogenous wastes in animal excrement.

Aviary: Refer to Multi-Tier.

Beak Treatment: A non-invasive procedure that uses specialized equipment (i.e. infra-red) that results in blunting of beaks.

Beak Trimming: Removal of a portion of the beak, usually with a specialized instrument that simultaneously cuts and cauterizes (e.g. hot blade).

Bedding: Loose material such as wood shavings or chopped straw that is added to housing environments.

Biosecurity: Measures designed to reduce the risk of introduction, establishment, and spread of animal diseases, infections, or infestations to, from, and within an animal population.

Bird: A chicken used in egg production of any age, size, or weight.

Brooder: A heated area of the barn to which chicks can go for warmth. See also Dark Brooder.

Cages with Furnishings: Enriched or furnished cages that were installed prior to this Code’s effective date and that do not meet this Code’s final requirements for Enriched Cages.

Cannibalism: A behaviour problem in which a bird pecks and consumes the flesh of another bird.

Carts: Portable wheeled devices that are used to move birds in an upright position from barns to transport vehicles. They can also be referred to as dolly or pullet carts.

Chick: A young bird from the time of hatch up until the point it is fully feathered, which is usually between 14 to 21 days of age.

Competent: Demonstrated skill and/or knowledge in a particular topic, practice, or procedure that has been developed through training, experience, or mentorship, or a combination thereof.

Container: Portable enclosures that are used to transport pullets and end-of-lay hens.

Conventional Cage: A wire mesh enclosure for housing laying hens with equipment for provision of water, automated feeding, and egg collection. Also referred to as unfurnished cage.

Crate: A portable container designed and constructed specifically for transporting pullets and hens.

Dark Brooder: A warm, dark, enclosed resting area for chicks that is clearly distinct from surrounding well-lit activity areas.

Dark Period: No more than 20% of the light intensity of the light period.

Dust Bathing: A special sequence of behaviour patterns that functions to clean the feathers and improve their insulative value. Depending on the substrate, it may also remove parasites from plumage.

End-of-Lay Hens: Egg laying poultry that have reached a timed point in their egg-laying cycle beyond which productivity significantly declines and they are removed from production.

Enriched Cage: A wire mesh enclosure outfitted with perches, nest area, scratch area, and more head room compared to a conventional cage; group sizes in furnished cages can range from 10 to over 100 hens, depending on the model. Also referred to as furnished cage or colony cage.

Enrichment: Enhancement of a bird’s physical or social environment that adds complexity.

Euthanasia: The process of ending the life of an individual bird in a way that minimizes or eliminates pain and distress. It is characterized by rapid, irreversible unconsciousness (insensibility), followed by prompt death.

Feather Pecking: A behaviour problem in domestic birds that involves a bird pecking (or plucking) the feathers from flock mates or herself.

Forage/Foraging: The behaviour patterns involved in searching for and consuming food.

Free-Range: A system where laying hens are allowed access to an outdoor pasture or range area.

Free-Run: A system where birds roam freely inside a barn but do not have access to the outdoors. Also referred to as barn systems.

Hen: A female domestic fowl that has reached sexual maturity (i.e. begun to lay eggs).

Insensible/Insensibility: The point at which an animal no longer has the ability to perceive and respond to its environment (e.g. light).

Litter: The combination of bedding and/or bird excreta, feathers, feed, dust, and other materials on floors of bird housing systems.

Litter Space: A solid floor surface with the ability to hold or contain litter/substrate.

Moulting: A natural seasonal event in which birds substantially reduce their feed intake, cease egg production, and replace their plumage. Induced or controlled moulting is a process that simulates natural moulting that extends the productive life of hens (1).

Multi-Tier: A non-cage system where nest, perching, and food and water resources are located on multiple elevated tiers. Also referred to as aviary systems or aviaries.

Non-Cage Systems: Systems that include single-tier (free-run, floor, or barn), multi-tier (aviary), and free-range, and do not use cages to house birds.

Non-Penetrating Captive Bolt: A specially designed device used for stunning and euthanasia that propels a blunt bolt with great force which, when applied in the correct position, causes immediate loss of sensibility.

On-Farm Depopulation: An on-farm practice that involves killing entire flocks or large numbers of birds.

Osteoporosis: A condition involving loss of bone mass leading to bone fragility and risk of fracture.

Perch: A structure, usually in the form of a narrow rod, that allows hens to wrap their toes around it and that is elevated a minimum of 1.3 cm (0.5 in) above the floor, which birds can use to sit or roost above the floor.

Pullet: A young female domestic fowl from the point it is fully feathered and that has not yet reached sexual maturity (i.e. begun to lay eggs).

Ramp(s): A ladder or narrow piece of plastic or wire mesh affixed to a tier frame at varying heights and at angles that do not exceed 45 degrees.

Range: The outdoor area to which birds may have access from indoor production systems.

Rearing: The phase during which chicks and pullets are cared for prior to reaching sexual maturity (i.e. begun to lay eggs).

Re-Tooling: A major renovation or overhaul of existing housing systems and/or strutures that is not part of normal or routine repair or maintenance. The addition of enrichments or furnishings that were not included when housing systems were installed is not considered to be re-tooling.

Roost: When a bird rests or sleeps on a perch.

Shackle Carts: Portable wheeled devices that are used to move birds in an inverted position from barns to transport vehicles.

Single-Tier: A non-cage system where nests, perches, and feed and water resources are located on only one level. Also referred to as floor housing.

Terrace: An additional flat plastic or wire platform in non-cage systems that may or may not be located within the main tier structure that birds use to move between tiers.

Tier: Any fixed floor level that is above the ground floor and is located directly above a manure belt or manure storage.

Training: The act that aims to impart skills and/or knowledge in a formal or informal manner (e.g. through mentoring) that results in the recipient’s understanding and/or ability to perform assigned tasks.

Unfit for Transport: A bird with signs of infirmity, illness, injury or of a condition that indicates that it cannot be transported without suffering (32).

Unfurnished Cage: Refer to Conventional Cage.

Useable Space for Chicks and Pullets: Includes the main floor, litter area, elevated terraces, plus any elevated tiers with a height of at least 45.0 cm (17.7 in) to which birds have continual access. Space under offset elevated terraces counts as useable floor space.

Useable Space for Laying Hens: Includes the main floor and litter area, plus any elevated floor areas/ tiers with a height of at least 45.0 cm (17.7 inches) to which birds have continual access, but excludes nest areas and any outdoor area, if applicable. Pertains to non-cage systems.

Section 1 Pullet Housing and Rearing

While this section covers some aspects of pullet rearing, all other sections in this Code, with the exception of Section 2: Housing Systems for Layers, apply to all birds, including chicks and pullets.

1.1 Pullet Housing

All housing systems for pullets include both welfare benefits and welfare challenges. In all systems, welfare improvements can be made by paying close attention to the specifics of the housing design, management practices, and choice of strain (2). It is critical that pullets destined for aviary systems during the laying phase be reared in systems with similar features. This helps to ease the transition to the lay barn, reduces problems associated with fearfulness, and enhances physical development (2).

Birds kept longer in rearing systems with litter need more litter space as they approach start of lay to support behavioural changes that occur at the start of egg production.

1.1.1 Housing Equipment: Design and Construction

Housing needs to protect the birds from anticipated environmental conditions, including normally-expected changes in temperature and precipitation, as well as predatory animals. Premises and equipment need to be maintained in clean and orderly fashion to eliminate any refuge for rodents, wild birds, and other animals that could introduce diseases to the flock.

REQUIREMENTSMaterials used in the construction of housing and equipment to which birds have access must not be harmful or toxic to the birds, and must be able to be thoroughly cleaned and maintained. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

when designing barns and equipment, take into consideration how birds will be inspected and handled in all areas.

1.1.2 Flooring

Layer pullets may be reared on wire, slats, or litter. Litter is preferred for rearing chicks. Floor coverings provide foot support, offer opportunities for natural behaviours such as scratching, foraging, and dust bathing, and promote optimum intestinal health.

REQUIREMENTSFlooring must be designed, constructed, and maintained in a manner that supports the birds’ feet and does not contribute to trapping, injuries, or deformities to the birds’ legs, feet, and/or toes. Housing system floors must be designed and maintained to prevent manure from birds in upper levels from dropping on birds enclosed directly below. Existing flow-through pullet cage systems must be replaced by January 1, 2020. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- ensure that the gaps between floor wires do not exceed 2.5 cm (1.0 in)

- use appropriate floor covering until birds reach a size suitable for the flooring

- choose a floor covering that promotes foraging and scratching (e.g. newspaper, paper plates, fibre egg trays).

1.1.3 Feeders and Waterers

Chicks and pullets have access to feed at all times so it is not necessary for all birds to feed simultaneously. When calculating the feed space, the age of the birds, their body weight and other factors need to be taken into consideration. The feed trough provides access on one side or two sides, depending on the design of the housing. The length of the feeder trough will depend on whether birds can access it only on one side or on both sides.

2025 Amendment: Only the round feeder space requirements have been amended. Research shows that limited feeding space can result in competition and aggression at the feeders (43). If competition and/ or aggression is observed, steps should be taken to mitigate competition (e.g., management practices) or increase feed space on a per-bird basis (e.g., add feeders; remove birds).

Scientific evidence shows that synchronization of feeding behaviour results in a maximum of 70% of hens or pullets eating at once, especially in large groups (43).

REQUIREMENTSFeed space and waterers (e.g. cups, nipple drinkers) must be provided as indicated in Table 1.1. All birds must have access to at least 2 waterers (e.g. cups, nipple drinkers) in case one breaks down. Automated feeding systems must be designed and utilized in ways that minimize the likelihood of chicks getting caught in them. |

Table 1.1: Minimum Feed Space and Maximum Birds per Waterer.

Bird Type/Age | Minimum Linear Feeder | Minimum Round Feeder | Minimum Water Space/Bird | Maximum Number of Birds per Waterer |

Chicks: 0 to 2 weeks | 1 cm (0.4 in) | 0.5 cm (0.2 in) | Linear:

| 30 |

Pullets: 2 to 8 weeks | 2 cm (0.8 in) | 0.9 cm (0.4 in) | 24 | |

Pullets: 8 weeks to Laying Barn | 4 cm (1.6 in) | 1.8 cm (0.7 in) | 12 |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- limit the distance that birds need to travel to access feed and water to 8.0 m (26.2 ft)

- monitor feeding behaviour for competition and aggression and add feed space on a per-bird basis if either is observed

- incorporate management strategies to ensure that feed augers are triggered regularly to ensure that fresh feed is available in all pans (e.g., lighting, manually triggering) when round feeders are used.

1.1.4 Space Allowance

Space allowance is typically measured and described as a minimum amount of useable area (cm2 or sq in) allocated to each bird. Space should be provided based on the age and expected size/weight of the birds when they are transferred to the layer barn. Space allowance needs to increase as the birds approach their mature weight. Therefore, space allowances for chicks, young pullets, and older pullets need to be adjusted as the birds grow.

When calculating space allowances in multi-tier rearing systems, the space beneath the first elevated tier is not considered useable space, unless the height allows birds to stand upright and birds have continuous access to the area. Refer to the Glossary for the complete definition of Useable Space for Chicks and Pullets.

2025 Amendment: Space allowances have been amended for pullets that are older than 8 weeks and housed in multi tier systems only (refer to Table 1.5). This amendment is intended to address the immediate need of producers who are considering rebuilding or replacing pullet housing that was in use prior to the amendment. As minimum space allowance requirements are a critical factor when designing barns, this amendment will only establish a timeline to increase minimum pullet space allowances for new holdings for which the building process commenced after the publication date of this amendment.

While the minimum space allowance requirement will apply to all holdings at some point in the future, the transition timeline for barns built before the amendment publication date will be decided by the Code Committee that is established to oversee the full Code update in or around 2028. At that time, it is expected that additional data will be available to help inform that decision, ensuring that housing conversions are managed responsibly with consideration for animal health, welfare, productivity, and the ongoing demand for eggs. In the meantime, pullet growers are strongly encouraged to increase space allowance over that currently required where feasible for pullets housed in multi-tier systems from 8 weeks of age.

Research shows that the physical space occupied by pullets is different for brown and white strains (43). At 18 weeks of age, the area covered during standing and sitting, respectively, averaged 434.5 cm2 (67.3 sq in) and 456 cm2 (70.7 sq in) for brown-feathered strains, and 361 cm2 (56.0 sq in) and 380 cm2 (58.9 sq in) for white-feathered strains (43).

Pullets that are transitioned to the layer barn after 17 weeks of age are at greater risk for poor welfare due to physiological and behavioural changes associated with the onset of lay (e.g., risk of smothering, egg peritonitis, mislaid eggs). For that reason, a new Recommended Practice has been added and elevated (Table 1.6) to prominently reinforce the importance of providing additional space for birds that remain in the pullet barn after 17 weeks of age. It is expected that this Recommended Practice to increase minimum space allowance for older pullets will become a Requirement when the full Code is updated in or around 2028.

REQUIREMENTSBirds must be able to stand fully in an upright position within the enclosure. Each bird must be provided with minimum space allowances as outlined in:

For Multi-Tier Rearing Systems installed prior to August 1, 2025, each bird must be provided with a minimum space allowance and applicable litter space as outlined in Table 1.4 (Multi- Tier Rearing Systems from 8 weeks of age – Barns in use prior to August 1, 2025). For Multi-Tier Rearing Systems for which new construction or re-tooling, including the phases of design, application, approval, planning, and installation, was initiated after August 1, 2025, each bird must be provided with a minimum space allowance and applicable litter space as outlined in Table 1.5 (Multi-Tier Rearing Systems from 8 weeks of age – New Construction). In Single-Tier Rearing Systems, each pullet from 8 weeks of age until transfer to the laying barn must be provided with a minimum of 696.8 cm2 (108 sq in / 0.75 sq ft) of useable space. |

Table 1.2: Minimum Required Space Allowance for Chicks and Pullets housed in Pullet Cages (Per Bird).

| Bird Type/Age | Minimum Space Allowance (Per Bird) | |

| Chicks: 0 to 2 weeks | 64.5 cm2 | 10.0 sq in |

| Pullets: 2 to 8 weeks | 129.0 cm2 | 20.0 sq in |

| Pullets: 8 weeks to layer barn | 283.9 cm2 | 44.0 sq in |

Table 1.3: Minimum Required Space Allowance for Chicks and Pullets while enclosed in Multi-Tier Rearing Systems to 8 weeks of age (Per Bird).

| Bird Type/Age | Minimum Space Allowance (Per Bird) | |

| Chicks: 0 to 2 weeks | 64.5 cm2 | 10.0 sq in |

| Pullets: 2 to 8 weeks | 129.0 cm2 | 20.0 sq in |

Table 1.4: Minimum Required Space Allowance for Pullets housed in Multi-Tier Rearing Systems from 8 weeks of age to layer barn (Per Bird) – Barns in use prior to August 1, 2025.

| Pullet Age | Total Minimum Useable Space | Minimum Space Allocated to System | Minimum Space Allocated to Litter | |||

| 8 weeks to layer barn | 342.0 cm2 | 53.0 sq in | 283.9 cm2 | 44.0 sq in | 58.1 cm2 | 9.0 sq in |

Table 1.5: Minimum Required Space Allowance for Pullets housed in Multi-Tier Rearing Systems from 8 weeks of age to layer barn (Per Bird) – New Construction or Re-Tooling initiated after August 1, 2025.

| Pullet Age | Total Minimum Useable Space | Minimum Space Allocated to System | Minimum Space Allocated to Litter | |||

| 8 to 17 weeks | 464.5 cm2 | 72.0 sq in | 283.9 cm2 | 44.0 sq in | 141.9 cm2 | 22.0 sq in |

| 17 weeks to layer barn | 464.5 cm2 | 72.0 sq in | 283.9 cm2 | 44.0 sq in | 141.9 cm2 | 22.0 sq in |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

Table 1.6: Minimum Recommended Space Allowance for Pullets housed in Multi-Tier Rearing Systems (Per Bird).

| Pullet Age | Total Minimum Useable Space | Minimum Space Allocated to System | Minimum Space Allocated to Litter | |||

| 8 to 17 weeks | 464.5 cm2 | 72.0 sq in | 283.9 cm2 | 44.0 sq in | 141.9 cm2 | 22.0 sq in |

| 17 weeks to layer barn | 541.9 cm2 | 84.0 sq in | - | - | 180.6 cm2 | 28.0 sq in |

- move pullets that are reared in multi-tier systems to layer barns when they reach maturity (~17 weeks of age), since the risk of smothering increases after they begin to lay eggs

- for pullets that are transitioned to the layer barn after 17 weeks of age, provide a minimum of 541.9 cm2 (84.0 sq in) of useable space per bird. Refer to Table 1.6

- increase litter space for pullets that are approaching maturity (i.e., egg production)

- increase space allowances for pullets when finishing will take place during hot weather periods

- restrict chicks housed in single-tier rearing systems to a small area of the barn that is close to feed, water, and heat during brooding.

1.1.5 Special Considerations for Multi-Tier Rearing Systems

Birds can be restricted from accessing space beneath the first elevated tier to train them to use the system during both the rearing and laying phases. Chicks and pullets that “hide” under the system may not access feed and water as often as they need to, and as a result may become compromised.

Additional space is necessary from 17 weeks of age to prevent smothering that can result as the litter area becomes attractive close to the onset of lay.

REQUIREMENTSTiers must be arranged to prevent droppings from falling directly on levels below. The number of tiers in a vertical plane (i.e., directly above each other) must not exceed 3 where the ground level is not considered to be one tier. Feed and water must be provided on more than one elevation of the system, and must not be provided on the ground level. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide sufficient space in multi-tier rearing systems to allow birds to roost and rest and so that they learn to come off the floor at night

- provide lighting beneath the first elevated tier when birds are provided access to this area

- provide sawdust, scratch paper, or suitable substrate for foraging to chicks from 1 day of age

- increase litter space for pullets that are approaching maturity (i.e. egg production)

- move pullets that are reared in multi-tier systems to layer barns when they reach maturity (~17 weeks of age), since the risk of smothering increases after they begin to lay eggs

- utilize strategies to encourage birds to use platforms (e.g. locate feed/water on platforms).

1.1.6 Perches

Birds have to learn to perch (2). Depending on perch height, chicks begin perching at around 7 to 10 days of age, and the amount of time spent perching steadily increases over time (2)(3). Pullets are more likely to use perches if they are introduced to them at an early age (3). Conversely, birds reared without perches have difficulty adapting to non-cage systems during lay (2).

Access to perches during rearing has been shown to increase nest use and decrease cloacal cannibalism during lay. Hens that were reared with perches have stronger bones. The inclusion of perches during the rearing phase promotes bird activity, can help to develop bone strength, can assist with the birds’ ability to adapt when they are transferred to the laying barn, and can assist in reducing the number of floor eggs during the laying phase.

Access to perches and more complex environments (e.g. ramps, ladders, elevated terraces) during rearing is critical for birds destined for non-cage multi-tier systems, because feed and water is provided on elevated tiers. Perching is beneficial for birds destined for all non-cage systems; however, in single-tier systems, food and water are provided at ground level. Communication and coordination between pullet growers and egg farmers can help ease the transition to the layer barn. Refer to Section 5.1: Pullet Sourcing and Transition to Lay.

The following requirements apply to any type of pullet housing system where perches are provided, except where specific housing systems are specified.

REQUIREMENTSPerches must be provided to chicks reared in multi-tier systems from 1 day of age. Terraces and/or elevated perches at varying heights must be provided from no later than 8 weeks of age in multi-tier rearing systems. Perches must be constructed of materials that are easily cleaned and do not harbour mites. Perches must be designed to prevent injury to pullets that are mounting or dismounting as well as to any pullets nearby. Perches must be positioned to prevent trapping and allow access to feed and water. Perches must be positioned to minimize fecal fouling of birds, feeders, or drinkers located below them. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide perches to pullets that are destined for single-tier laying systems

- cap hollow ends of perches

- provide terraces and elevated perches at varying heights as early as possible in multi-tier systems.

1.2 Receiving and Brooding Chicks

Special care needs to be taken to ensure that newly-arrived chicks settle in well to their new environments. They need to be protected from abrupt changes in temperature and be able to locate feed and water.

Feedback on chick condition, mortality, and performance can help hatcheries evaluate their management and transport protocols.

Evaluation criteria could include:

- alertness: an alert chick has wide-open bright eyes and appears curious

- vigour: a vigorous chick is instantly active when disturbed and shows no signs of weakness or unthriftiness

- condition: a chick in good condition will be firm. The fluff will not be matted, there are no signs of dehydration, and the navel is healed. An unhealed navel can become an early access route for bacterial infections. Chicks must be handled in order to be evaluated for condition

- body Temperature: the normal body temperature for chicks is 40.0 – 40.7°C (104.0 – 105.3°F)

- behaviour: chicks should not show signs of distress (e.g. huddling, open-mouth breathing, excessive vocalization)

- normalcy: a normal chick has no apparent deformity or abnormality such as twisted toes or beaks, crippled or straddled legs, etc.

REQUIREMENTSFacilities must be prepared (i.e. heat, clean, feed, water, bedding) in advance of receiving chicks so that they can be placed promptly after arrival. Farm personnel must be present at the time of delivery and placement, and must assess the physical condition of the chicks. Steps must be taken to prevent chicks from becoming chilled or overheated during unloading and brooding. All chicks must be kept, treated, and handled in ways that prevent injury and minimize stress. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- handle boxes of chicks gently and in a level position

- inspect chicks immediately upon arrival. Document any problems and provide feedback to the hatchery

- provide supplementary feed and water sources (trays or paper) to ensure that chicks can locate feed easily. Remove supplementary water sources gradually as birds learn to drink from nipples

- ensure that chicks can access water and that it is at the appropriate height and pressure

- check chicks more than twice daily during brooding

- increase the frequency of monitoring if any of the following are observed: huddling or piling, inactivity, high early mortality, or problems with equipment

- prevent chicks from crowding or piling on top of each other in the corners of floor pens

- confirm brooding area temperatures at chick level.

1.3 Lighting

Supplemental heat is essential in maintaining chicks’ body temperature during the first few weeks of life when natural brooding is not utilized. However, the use of radiant heat lamps results in constant exposure to light. Continuous light can negatively impact eye development of newly hatched chicks (4) and disrupts rest, which affects the synchronization of chicks’ activities (5).

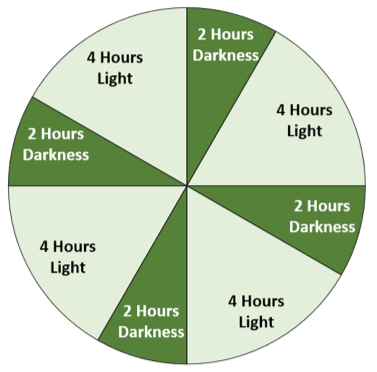

Some chicks continue to rest after arrival from the hatchery, while others seek out food and water. An intermittent lighting program (refer to Figure 1.1) divides the day into resting and activity phases and can assist with synchronising chick activity to improve food and water intake as weaker chicks are stimulated by stronger ones to eat and drink (6). Synchronizing activity has been shown to promote better rest, and can reduce the development of feather pecking by separating active and inactive birds (2). In addition, an intermittent lighting program typically results in more uniform flock behaviour (5) as well as lower mortality rates.

In commercial settings, the positive welfare outcomes associated with brooding by hens can be achieved by providing simulated brooding cycles of light and dark periods, and/or by providing dark brooders, which are warm, dark, and enclosed areas that may simulate the effects of a brooding hen (2). Dark brooders have been found to have long-term preventative effects on feather pecking and cannibalism, and can improve behavioural synchrony between birds, reduce disturbances during resting, and result in calmer birds (3).

Ideally, the time of day for start of the light period (lights on) during rearing should be matched to the start of the light period in the laying barn (2). Simulating the gradual oncoming of night (dusk) by gradually lowering lights at night will help pullets in non-cage systems locate a suitable perch for the night, or move up onto tiers while visually capable (7). In addition, gradually increasing lighting in the morning (e.g. using dawn to dusk lighting) can enhance welfare by allowing birds to gradually wake up and leave perches.

Communication and coordination between pullet growers and egg farmers can help ease the transition to the layer barn. Refer to Section 5.1: Pullet Sourcing and Transition to Lay for more information.

| Figure 1.1: Example of an Intermittent Lighting Program |

|

REQUIREMENTSChicks must be provided with a minimum of 2 consecutive hours of darkness in each 24 hour period. The dark period must be gradually increased to a total minimum of 6 hours in each 24 hour period by 2 weeks of age. Chicks must be provided with a minimum of 16 hours of light in each 24 hour period up to 2 weeks of age. Chicks must be provided with light intensities of at least 20 lux (2 foot candles) for at least the first 7 days that allow them to easily locate feed and water. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- simulate brooding cycles for chicks by implementing cycles of light and dark periods, and/or by providing dark brooders. Utilize an intermittent light/dark schedule for chicks (e.g. 2 hours darkness followed by 4 hours light) to simulate a brooding cycle and to synchronize activities.

1.4 Pullet Rearing and Reducing Fear

The early experiences of chicks and pullets affect the welfare of the young bird and can impact the health, behaviour, fearfulness, and welfare of the laying hen (2). Fear can impair the ability of birds to adapt to new environments, which can make it difficult for them to utilize new resources or to interact with other birds or people (2). Moreover, fearfulness in young birds is also associated with feather pecking behaviour.

Consistent management practices during both the rearing and laying phases will help birds adapt to the new barn (2).

Strategies to reduce fear during rearing include providing complex rearing environments, regular exposure to humans, gentle handling, and intermittent lighting strategies or the use of dark brooders (2). Fearfulness can also be reduced by providing enrichments such as rattles, balls, colourful plastic bottles, strings, or drawings on the wall (8) as well as exposing chicks to a radio playing a human voice (9).

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- develop protocols to ensure that stockpersons have frequent and calm interactions with chicks and pullets regardless of what type of housing system is used

- give an audible signal to chicks and pullets before entering the barn (e.g. knock lightly on door)

- provide enrichments to chicks and pullets, which may help to reduce fear (e.g. play music, hang objects).

Section 2 Housing Systems for Layers

All housing systems for hens include both welfare benefits and welfare challenges. In all systems, welfare improvements can be made by paying close attention to the specifics of the housing design, management practices, rearing conditions, and choice of strain (2).

Hens are motivated to nest, forage, perch, and dust bathe (2). Other natural comfort behaviours include movement and activities such as stretching legs and wings (2). It is important that rearing environments are taken into consideration when transitioning to the layer barn. Refer to Section 5.1: Pullet Sourcing and Transition to Lay for more information.

2.1 Housing and Equipment: Design and Construction

Housing needs to protect the birds from anticipated environmental conditions, including normally-expected changes in heat, cold, and precipitation, as well as predatory animals. Premises and equipment need to be secure and maintained in clean and orderly fashion to manage the risk of disease. It is also important to design housing systems in such a manner that permits thorough inspections of birds, access to sick and injured birds, as well as the ability to remove dead birds. It is important that barns are of sound construction and well maintained. Smooth, hard, and impervious surfaces will enable effective cleaning and disinfection (10).

REQUIREMENTSMaterials used in the construction of housing and equipment to which birds have access must not be harmful or toxic to birds, and must be able to be thoroughly cleaned and maintained. Openings and access points must permit placement of pullets and removal of full grown layers of all breeds without injury. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- when designing barns and equipment, take into consideration how birds will be inspected

- site barns on well-drained land

- use concrete to construct ground-level floors

- design, construct, and maintain buildings to prevent access by predators and wild birds, and to deter rodents

- utilize migration fences to divide large flocks into smaller groups.

2.2 Flooring

There are a variety of flooring types used for layer hens in both cage and non-cage systems. The flooring design and construction, as well as cleanliness, can have an impact on hen welfare from both health and behaviour perspectives. Risks of foot problems are linked to all types of housing systems, but the type and severity can differ between systems.

REQUIREMENTSFlooring must be designed, constructed, and maintained in a manner that does not contribute to injuries or deformities to the birds’ legs, feet, and/or toes. All slatted, wire, or perforated floors must be constructed to support the forward facing claws. The slope of any slat or wire floor or solid surface that is included in the useable space calculation must not exceed 8 degrees (14%). Housing system floors must be designed and maintained to prevent manure from birds in upper levels from dropping on birds enclosed directly below. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- ensure that the gaps between slats and wire do not exceed 2.5 cm (~1.0 in).

2.3 Feeders and Waterers

Hens have access to feed at all times so it is not necessary for all birds to feed simultaneously. When calculating the feed space, the age of the birds, their body weight, and other factors need to be taken into consideration. The feed trough provides access on one side or two sides, depending on the design of the housing. The length of the feeder trough will depend on whether birds can access it only on one side or on both sides. If growth or egg production rates are lower than expected, it may be because there are too many birds for the available space, resulting in birds crowding at the feeders.

2025 Amendment: Only the round feeder space requirement has been amended. Research shows that limited feeding space can result in competition and aggression at the feeders (43). If competition and/ or aggression is observed, steps should be taken to mitigate competition (e.g., management practices) or increase feed space on a per-bird basis (e.g., add feeders; remove birds).

Scientific evidence shows that synchronization of feeding behaviour results in a maximum of 70% of hens or pullets eating at once, especially in large groups (43).

REQUIREMENTSAccessible feed space must be provided at a minimum rate of 7.0 cm (2.8 in) per bird for linear feeders1 and 2.8 cm (1.1 in) for round feeders. All birds must have access to:

a Accessible feed space is calculated on a per bird basis and can include only one side of the trough, or both sides if the trough is located in such a way that birds have access to it from both sides. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide additional accessible feed space where feeding strategies (e.g. feeders are not run during peak nesting hours) are used that result in more hens feeding simultaneously

- position feeders and waterers in such a way to prevent birds from defecating in them

- use well-designed drinkers, and ensure that they are used and operated in such a way so as to avoid leaks and excessive spillage

- position nipple drinkers and cups a minimum of 15.0 cm (5.9 in) apart from each other on each water line

- add more feed space if over-crowding and/or competition at the feeders is observed

- set feed trough heights so that birds do not have to perch to feed (i.e. can stand on the floor).

2.4 Enriched Cage and Non-Cage Housing Systems

There are welfare trade-offs associated with each type of housing system. Hens raised in non-cage systems generally have greater freedom of movement and have more opportunity to engage in natural behaviours than cage-housed birds. However, non-cage systems need to be carefully managed to limit risks of disease, injuries, injurious pecking (11), and mortality (2). Enriched cages generally maintain the health and hygiene benefits associated with conventional cages while providing amenities that allow hens to nest and perch and space to move around and stretch wings. However, while existing enriched cages offer some opportunity for foraging and dust bathing, they do not fully support that behaviour (2). In all systems, housing design, management, rearing conditions, and choice of strain are all factors that impact hen welfare (2). The industry is committed to continuing to support research so that hens in all housing systems are provided with opportunities to express natural behaviour and health and mortality risks are minimized. |

Furnishings and enrichments provide opportunities for hens to perch, nest, forage, and dust bathe, all of which are considered natural behaviours that hens are strongly motivated to perform (2).

Also known as furnished cages, enriched cages are larger than conventional cages, and can house from 10 to 100 hens in each cage. Enriched cages provide hens with more space and the resources to engage in a wider range of natural behaviours (2). Existing furnished or enriched cages may not meet the final requirements of this Code, and as such, are referred to as Cages with Furnishings.

Non-cage systems, also referred to as free-run or cage-free systems, typically house larger groups of hens than cage systems, and may or may not be combined with access to the outdoors. Indoor non-cage systems may consist of a single-tier or multi-level tiers, which can also be referred to as multi-tier or aviary systems. Indoor systems protect birds from predators and the outside environment.

2.5 Transitioning from Conventional Cages

Unfurnished, or conventional cages, are enclosures with wire mesh and sloping floors that typically house 4 to 8 hens. These cages provide a controllable environment that protects hens from a range of health and injury problems. However, hens are restricted from engaging in many natural behaviours due to limited space and amenities (11), and, as a result, conventional cages have begun to be phased out in Canada.

In order to facilitate a smooth changeover, transitional and final requirements are included in each of the following sub-sections as a way to improve the welfare for all hens regardless of the housing system type that is utilized. This approach recognizes that there may be structural and other challenges that may impede the ability of producers to refurbish existing installations to this Code’s final housing standards until such time that barns are completely renovated or rebuilt. As such, the interim or transitional allowances apply to existing installations up until the time that the barn is renovated or replaced, unless otherwise specified.

For more information, refer to Appendix A: Transitional and Final Housing Requirements for Enriched Cages and Appendix B: Transitional and Final Housing Requirements for Non-Cage Housing.

The following sections detail the effective dates for all transitional requirements. Some requirements (identified by “(F)”at the end of the requirement) are also included in the Final Requirements. Inclusion in the Transitional Requirements mandates modifications to existing housing systems prior to the final transition date.

The transition of Canada's hens from conventional to enriched housing systems is a complex undertaking that requires a nationally coordinated approach with participation and support from industry and all stakeholders. For example, to support hen welfare needs in enriched systems in layer barns, significant changes to pullet rearing housing systems are also necessary. In addition, since egg farmers will have to take hens out of production while new housing systems are being built, there is a need to coordinate housing conversions to ensure that market demand for eggs can continue to be met. In addition, alternative housing systems to which hens will be moved present complex welfare trade-offs that must be considered from the perspectives of the housing structures, the furnishings, and management. This Code represents the first time in Canada that housing standards for enriched housing systems are clearly defined so that egg producers have both guidance and flexibility in meeting the welfare needs of hens. The industry commits to a minimum of 85% of hens to be transitioned from existing conventional cage systems to alternative housing systems that meet the requirements of this Code within 15 years, and will aim to transition 100% of hens within the same time frame. It is expected that 50% of birds will be transitioned within 8 years. The transition will be overseen by the industry and its stakeholders, and reviewed within 10 years to assess and evaluate the status of the transition. If any hens remain in conventional cages after 15 years, greater space allowance that represents as much as a 34% increase in space must be provided. Hens removed from these systems will move to enriched housing systems that meet the requirements of this Code. The transition strategy that the CDC has developed represents an organized approach that allows the industry to phase out conventional cages in an orderly manner that is practical, feasible, cost-efficient for farmers and consumers, and ensures that the market demand for eggs can continue to be met. The industry is committed to supporting ongoing and new research into providing birds with greater freedom of movement and more opportunities for engaging in natural behaviour, and to implement practical solutions as they become available. The outcomes of these shared endeavours will inform the next Code revision and/or possible amendments to this Code in the interim. |

REQUIREMENTSAll housing systems to which hens are transitioned must support nesting, perching, and foraging (pecking and scratching) behaviour. If any hens have not been transitioned from conventional cages by July 1, 2031, each of those hens still kept in conventional cages must be provided with a minimum space allowance in those systems of 580.6 cm2 (90.0 sq in), effective July 1, 2031. All hens must be housed in enriched cage or non-cage housing systems that meet this Code’s requirements by July 1, 2036. Enriched cages installed after January 1, 2032, must be designed to include amenities that provide hens with improved opportunities to forage and dust bathe. |

2.5.1 Space Allowance

Space allowance refers to the amount of space that is available on a per-bird basis. Sufficient space allowance provides hens with the opportunity to move around and engage in comfort behaviours (e.g. stretching, preening), as well as provides unrestricted opportunities for nesting, foraging, and dust bathing (2). When calculating useable space allowances for non-cage systems, interior measurements are used and areas allocated for nests are not included.

Currently, there are no clear conclusions to draw on with respect to flock sizes and stocking densities for non-cage systems (2). System designs, distribution of hens within a system, and environmental conditions have a greater effect on bird welfare than group size and stocking density (2). However, as space allowances increase, hens are able to engage in a greater range of behaviour patterns (2). Floor space requirements vary considerably depending on breed, ambient temperature, and whether any or all of the floor consists of wire or wooden slats. In general, the most space is required in systems with 100% litter floors, and least where the floor is entirely wire or slats.

FINAL SPACE ALLOWANCE REQUIREMENTSEffective for all holdings for which new construction or re-tooling, including the phases of design, application, approval, planning, and installation, was initiated after April 1, 2017:

|

TRANSITIONAL SPACE ALLOWANCE REQUIREMENTS aEffective for flocks placed after April 1, 2017:

Effective for flocks placed after January 1, 2020:

Effective for flocks placed after January 1, 2022:

a The inclusion of “(F)” at the end of a requirement indicates a Final Requirement that applies to flocks placed after the stated transitional date. |

2.5.2 Nesting

Nests are typically provided through the use of a curtained area or solid nest boxes. Both single bird nests and communal nests, which allow multiple hens to nest simultaneously, can be provided. Hens prefer smaller nests over larger communal nests (12). Competition for nest space depends on lighting programs, bird strain, as well as group size. For these reasons, a larger minimum nest space allowance is needed for non-cage systems to meet the birds’ tendency towards more group nesting behaviour.

Hens in furnished cages may benefit from providing more than one enclosed area for nesting that is distinct from the scratch area (13).

Mechanized nest boxes, which are used in some housing systems, need to be designed and maintained to protect hens from injury.

FINAL NESTING REQUIREMENTSEffective for all holdings for which new construction or re-tooling, including the phases of design, application, approval, planning, and installation, was initiated after April 1, 2017:

|

TRANSITIONAL NESTING REQUIREMENTSaEffective for flocks placed after April 1, 2017:

Effective for flocks placed after January 1, 2020:

Effective for flocks placed after January 1, 2022:

a Green shaded boxes indicate Final Requirements(also indicated by “(F)”) that apply to flocks placed after the stated transitional date. |

- evaluate nesting needs, taking into consideration bird strain and other factors, and adjust nest size and/or number and type of nests accordingly

- observe hens during peak nesting periods to determine if management practices (e.g. lighting programs, nest space/type) should be changed

- provide a greater number of smaller communal nests rather than a lower number of larger communal nests (12)

- position nest boxes in locations that are easily accessible to hens. For example, they should not be so high that injuries may occur as hens ascend or descend

- incorporate strategies to encourage hens to use the middle nests in rows of continual nests (e.g. create more corners by using partitions or cross-overs, provide extra substrate) (14)

- clean nests regularly to prevent the accumulation of manure

- keep nest litter, when used, clean, dry, friable, and moisture absorbent.

2.5.3 Perching

Perches provide opportunities for increased exercise and roosting off the ground at night, while also increasing vertical space (2). Perches improve bone strength, but can contribute to fractures and deformed keel bones (2). The shape, material, and cleanliness of perches can impact foot health.

Cross-wise perches and other perch arrangements that limit hen access reduce the available perch space (2). When calculating useable perch space, purpose-designed perches can include alighting rails in aviaries, but do not include feeder trough edges or slats. Refer to the Glossary for the complete definition of Perch.

FINAL PERCHING REQUIREMENTSEffective for all holdings for which new construction or re-tooling, including the phases of design, application, approval, planning, and installation, was initiated after April 1, 2017:

|

TRANSITIONAL PERCHING REQUIREMENTSEffective for flocks placed after April 1, 2017:

Effective for flocks placed after January 1, 2020:

a When calculating useable perch space, 30.0 cm (11.8 in) must be subtracted from the total linear length for each intersection of crossed perches when there is less than 19.0 cm (7.5 in) of vertical space between the intersecting perches. b Refer to Transitional Space Allowance(2.4.2) requirement, which mandates a higher space allowance effective January 1, 2020 when linear perch space per hen of less than 15.0 cm (5.9 in) is provided. |

- cap hollow ends of perches

- use perches that minimize keel, foot, and nail damage. Avoid sharp edges. Use oval or mushroom shaped perches

- use multiple perches with variable diameters

- locate perches at varying heights that allow birds to roost comfortably without coming into contact with the top of the cage

- limit the angles between perches at different heights to 45° or less

- limit the distance between perches at the same height to 1.0 m (39.4 in) or less

- position perches over slats or manure belts to avoid build-up of manure.

2.5.4 Foraging and Dust Bathing (Code Interpretation JAN 2019)

Foraging is a behavioural need that consists of pecking and scratching on a solid surface that is associated with searching for and ingesting food (2). Dust bathing is considered to be a behavioural need which is difficult to accommodate in some housing systems. Sprinkling feed intermittently on a pad as a substrate to accommodate both foraging and dust bathing may serve to meet the hens' behavioural needs. Increasing foraging opportunities by providing suitable substrate can reduce the incidence of feather pecking and cannibalism (9). Refer to Section 5.7.1: Feather Pecking and Cannibalism for more information.

Foraging sites in housing systems where litter is not used can include providing nutritional enrichment such as bales of hay or straw, insoluble grit, or oat hulls, or can be material that provides foraging opportunities.

Covering surfaces that hens scratch with an abrasive material can help to prevent overgrown claws. With appropriate substrate, hens are able to engage in dustbathing (9).

FINAL FORAGING AND DUST BATHING REQUIREMENTSEffective for all holdings for which new construction or re-tooling, including the phases of design, application, approval, planning, and installation, was initiated after April 1, 2017:

|

TRANSITIONAL FORAGING AND DUST BATHING REQUIREMENTSEffective for flocks placed after April 1, 2017:

Effective for flocks placed after January 1, 2022:

|

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- hang or wall-mount additional foraging sites in multi-tier systems

- locate the foraging area in such a way that hens can access it from as many sides as possible and allows hens to dust bathe as a group

- utilize smooth surfaces that can be easily cleaned (e.g. mats, pads)

- scatter feed or substrate in the foraging/dust bathing area

- avoid locating foraging/dust bathing areas under areas where birds can perch, or take measures to prevent birds from perching on structures above the foraging/dust bathing area

- provide a ramp between the scratch area and the slats to aid movement between the areas

- provide foraging sites that consist of nutritional enrichment such as bales of hay or straw, insoluble grit, or oat hulls

- inspect foraging material for quality, contaminants, and hazards prior to providing to hens

- provide a variety of foraging materials

- introduce ingestible foraging material gradually to the flock and provide in combination with insoluble grit.

2.6 Special Considerations for Multi-Tier Systems

A ramp between the scratch area and the slats aids movement between the areas and may help to reduce the risk of floor eggs, feather pecking, and bone fractures.

REQUIREMENTSBirds must be placed on the system near feed and water sources when moving birds to multi-tier systems. A minimum height of 45.0 cm (17.7 in) must be provided below the bottom of any tier. Tiers must be arranged to prevent droppings from falling directly on levels below. The number of tiers in a vertical plane (i.e., directly above each other) must not exceed 3where the ground level is not considered to be one tier. Raised tiers must have a system for removal of manure that does not interfere with the birds or cause injury. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide lighting beneath the first elevated tier when birds are provided access to this area

- use ramps or ladders with angles that are less than 45° to facilitate movement between levels

- remove litter from the floor level periodically to maintain the minimum height clearance of 45.0 cm (17.7 in)

- utilize one manure belt for each elevated tier.

2.7 Access to Outdoors

Free-range systems provide access to an outdoor, uncovered area, usually with some vegetation, to which hens have access via doors or pop holes in the wall. Outdoor ranges may also have a covered verandah. Free-range systems provide birds with access to the outdoors when the weather permits. Restricting birds from using the outdoor range may be necessary when birds are at risk for exposure to disease or other threats to health and welfare.

2.7.1 Housing and Range: Design and Construction

REQUIREMENTSBirds must have easy and continuous access to a structure that protects them from environmental conditions and meets the temperature and hygiene needs of the birds. Door openings from the barn to the range must be a minimum of 35.0 cm (13.8 in) high and 40.0 cm (15.7 in) wide and must be distributed throughout the barn so that all birds have access. There must be a means to restrict access to outdoors when bird health or welfare is at risk. Perimeter fencing must be provided and maintained to protect birds from ground predators. The openings to the range must be designed to minimize the adverse effects of weather to maintain good litter quality (Refer to Section 3.5: Litter Management). |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide one or more shade structures in the outdoor area

- provide openings along the entire length of the barn at a rate of 40.0 cm (15.7 inches) of width per 200 hens to encourage hens to use the range

- install eaves troughs and drainage to control and direct water runoff

- provide an overhang along with concrete, pea gravel, sand, or like material just outside the entrances/exits so as to reduce the potential for mud holes. This is particularly important in high rainfall areas

- minimize direct sunlight penetration into the barn through openings by using awnings or overhangs above the openings.

2.7.2 Range Management

There are additional challenges associated with raising birds in free-range systems, including pests, predators, the risk of disease transmission from other birds and animals, and the difficulty of sanitizing facilities.

REQUIREMENTSThe range area must be kept free of debris that may shelter pests. The outdoor range must be sited and maintained to manage range conditions that can negatively affect bird health or welfare. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- check to make sure that land is free of poisonous plants, dangerous chemicals, and disease-causing organisms that could impair the health of birds

- ensure that the majority of the range area is covered in vegetation

- ensure stocking density of range birds on pasture does not exceed the pasture’s ability to maintain vegetation

- rotate range areas if possible to allow vegetation to re-grow between flocks. This may also help to reduce the risk of disease (15)

- provide windbreaks where there is a likelihood of strong winds

- utilize strategies to reduce the risk of predation (e.g. use electric fencing outside enclosures, use fine netting over enclosures, bury portion of fence to prevent ground predators from entering, attach kites to barns and/or feeders to discourage aerial predators).

2.7.3 Feeders and Waterers: Access to Outdoors

Birds housed in free-range systems with access to outdoors should have the same feeding space and diet as birds housed in non-cage indoor systems. However, appropriate measures need to be taken to protect feed from adverse weather conditions to ensure that the nutritional integrity of the feed is not compromised.

REQUIREMENTSIf feed and water are provided outdoors, it must be in such a way that discourages access by wild birds. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- protect feed from adverse climatic conditions

- prevent access to potentially contaminated water sources

- for birds with access to the outdoors, provide feed and water indoors.

Section 3 Barn Environmental Management

Barns need to be capable of maintaining an environment that reduces the risk of either overheating or chilling of birds and that maintains suitable air quality. The heating and ventilation systems need to be considered together. A change in temperature will change ventilation requirements.

3.1 Ventilation and Air Quality

Ventilation provides fresh air and removes stale, contaminated air. It assists in managing temperature, humidity, noxious gases (e.g. ammonia, methane, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide), dust and other airborne particles, and affects litter quality.Birds can detect ammonia at 5 ppm and find it aversive at 20 ppm (16). Exposure to ammonia can impair health, reduce immune function, and contribute to feather pecking (16). Ammonia problems are more likely to occur in early morning and during the winter, when humidity levels may be higher.

Reliable tools to measure ammonia levels are necessary. Relying solely on smell is not sufficient since individuals’ sense of smell can become accustomed to the odour (17). Carbon dioxide levels could negatively affect bird behaviour if they exceed 5,000 ppm. The build-up of noxious gases is more of a risk when combustion-type heat systems are used.

Dust is a potentially harmful air contaminant, particularly in combination with ammonia and other gases. It may directly harm the respiratory tracts of poultry and also act in the transmission of infectious agents (16).

Water vapour from the respiration of birds and moisture from heaters produce humidity (18). Well-constructed buildings with good insulation can help to achieve good air quality and temperature control. The ideal relative humidity range for poultry is between 55% and 65% (18).

Internal air circulation is also a very important factor in that it helps to distribute fresh air and supplemental heat as well as to eliminate temperature differentials (18).

Sudden or extreme variations in barn conditions can be a source of stress to birds, and may contribute to feather pecking (19).

REQUIREMENTSEnvironmental control systems must be designed, constructed, and maintained in a manner that allows for fresh air and hygienic conditions that promote health and welfare for birds. Action must be taken to manage ammonia levels if they reach a harmful range (e.g. 20 to 25 ppm). |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- aim for a relative humidty level of between 50% and 70% as a primary step to maintaining good air quality

- remove manure as needed to control both humidity and ammonia levels

- monitor and record ammonia levels on a weekly basis. Increase monitoring frequency during cold and/or humid weather

- take steps to control ammonia levels from exceeding 20 ppm (8)(e.g. remove manure prior to cold weather, increase ventilation, adjust feed composition, apply manure treatments, gradually adjust temperatures to acclimatize birds to lower temperatures)

- utilize internal air circulation to help evenly distribute fresh air and supplemental heat.

3.2 Temperature

Optimal temperature ranges are not the same for all birds or stages of production. Breeder management guides are valuable resources. Comfort levels for birds can be affected by temperature, humidity, and air movement in the environment. Generally, birds can maintain their body temperature after the first few days of age through a variety of behavioural and physiological mechanisms. For that reason, from 6 weeks of age birds can tolerate wide ranges in temperature (20). For example, hens with access to the outdoors will increase their feed intake to compensate for lower ambient temperatures.

Bird behaviour can be used as a reliable indicator of thermal comfort. Signs that indicate that temperature is too high include:

- frequent spreading and flapping of wings

- panting

Conversely, signs that indicate a temperature is too low include:

- feather ruffling

- rigid posture

- trembling

- huddling or piling on top of each other

- distress vocalization

Newly hatched chicks have a poor ability to control body temperature and require supplementary heat to bring their environmental temperature up to their comfort range. When operating under conditions of minimum ventilation during chick start-up, there can be a build-up of CO2levels.

REQUIREMENTSTemperatures inside housing systems must be monitored on a daily basis. Temperatures inside housing systems must be maintained within a range that contributes to good health and welfare of the birds. Birds must be monitored for signs of cold or heat stress. Upon discovering birds showing signs of cold or heat stress, remedial action must be taken immediately. The environment for newly placed chicks must be pre-heated to breed-specific temperatures and maintained at a level that promotes good chick health and welfare. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- refer to Table 3.1 for general guidelines on temperature ranges for bird thermal comfort

- protect birds against cold drafts, cold areas, and extreme heat

- record minimum and maximum inside temperatures daily

- measure the temperature at bird level

- monitor for signs of cold or heat stress, particularly when ambient temperatures are extreme

- utilize temperature alarms that relay alerts if the temperature in barns deviates from set points (high and low)

- utilize override devices that allow operation of ventilation and/or heat systems in the barn in the event of a controller failure

- adjust temperature ranges for hens with significant feather loss to prevent cold stress

- provide supplemental heat in layer barns to maintain optimal air quality and temperature

- maintain temperatures inside housing systems throughout the growth cycle in accordance with breed-specific guidelines

- aim for a relative humidty level between 50% and 70% to assist birds with maintaining thermal comfort.

Table 3.1: Temperature Guidelines for Thermal Comfort for Birds by Age