Codes Of Practice

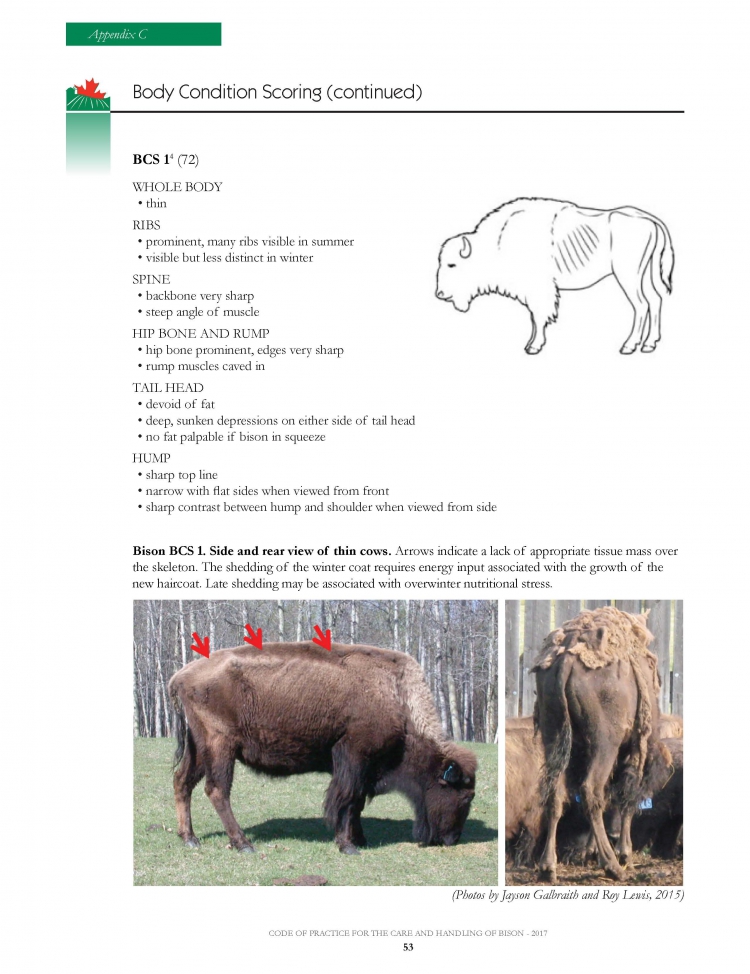

Developed through NFACC

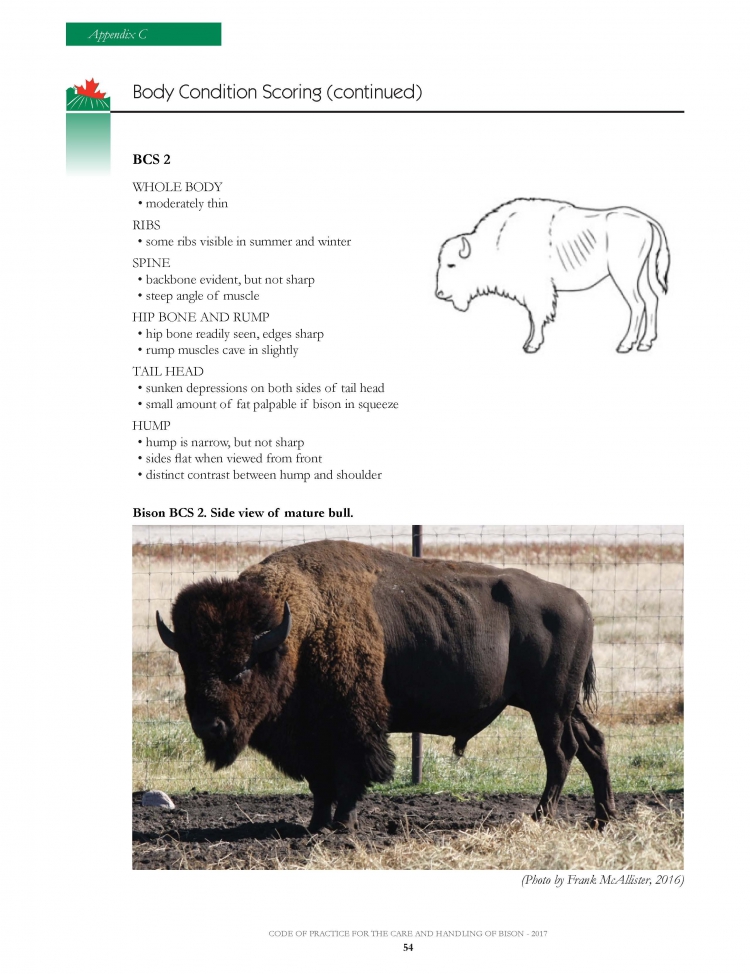

- Bison

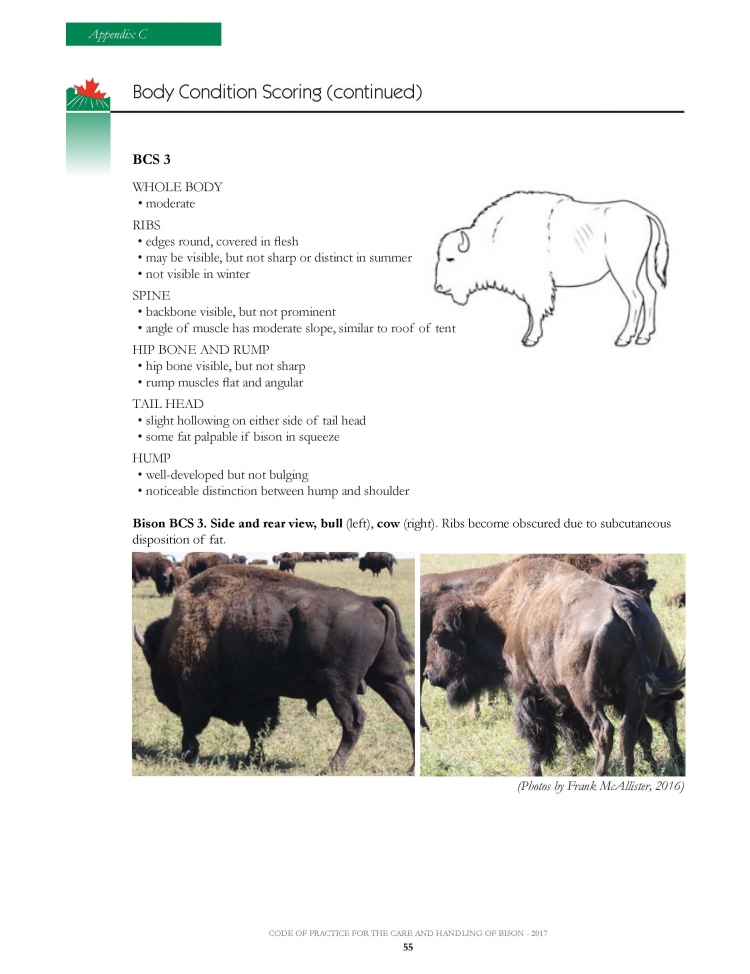

- Dairy Cattle

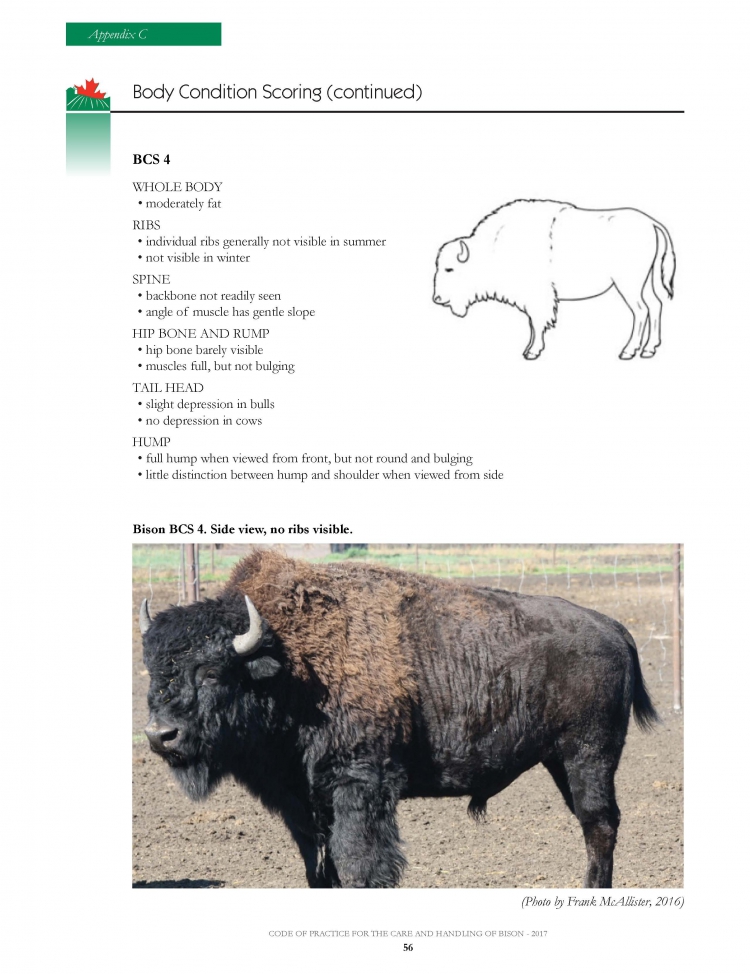

- Farmed Fox

- Farmed Mink

- Farmed Salmonids

- Goats

- Pullets and Laying Hens

- Rabbits

- Veal Cattle

Under Revision

Archived Recommended Codes of Practice

Code Development Process

Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Bison

| PDF |

ISBN 978-1-988793-04-7 (book)

ISBN 978-1-988793-18-4 (electronic book text)

Available from:

Canadian Bison Association

200 - 1660 Pasqua St., P.O. Box 3116, Regina, SK S4P 3G7 CANADA

Telephone: 306-522-4766

Fax: 306-522-4768

Website: www.canadianbison.ca

Email: info@canadianbison.ca

For information on the Code of Practice development process contact:

National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC)

Website: www.nfacc.ca

Email: nfacc@xplornet.com

Also available in French

© Copyright is jointly held by the Canadian Bison Association and the National Farm Animal Care Council (2017)

This publication may be reproduced for personal or internal use provided that its source is fully acknowledged. However, multiple copy reproduction of this publication in whole or in part for any purpose (including but not limited to resale or redistribution) requires the kind permission of the National Farm Animal Care Council (see www.nfacc.ca for contact information).

Acknowledgment

![]()

Funding for this project has been provided through the AgriMarketing Program under Growing Forward 2, a federal–provincial–territorial initiative.

Disclaimer

Information contained in this publication is subject to periodic review in light of changing practices, government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/or without seeking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the authors shall not be held responsible for loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Furthermore, the authors expressly disclaim all and any liability to any person, whether the purchaser of the publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, by any such person in reliance on the contents of this publication.

Cover image (top) courtesy of L.H. Trevor and Jodi Gompf, Bison Spirit Ranch, Manitoba

Cover Image (bottom) courtesy of Rod and Yvonne Mills YR Bison Ranch, Alberta

Table of Contents

| Preface | ||||

| Introduction | ||||

| Glossary | ||||

| Section 1 Animal Environment | ||||

| 1.1 | Grazing Environment | |||

| 1.2 | Pasture Management | |||

| 1.3 | Supplementary Feeding Areas | |||

| 1.4 | Fencing | |||

| 1.5 | Environmental Management | |||

| 1.6 | Safety and Emergencies | |||

| Section 2 Feed and Water | ||||

| 2.1 | Nutrition and Feed Management | |||

| 2.2 | Water | |||

| Section 3 Animal Health | ||||

| 3.1 | Health Management | |||

| 3.2 | Sick, Injured, and Compromised Bison | |||

| 3.3 | Health Conditions Related to Finishing | |||

| 3.4 | Nutritional Disorders Associated with High Energy Feeding | |||

| Section 4 Herd Management | ||||

| 4.1 | Management Responsibilities | |||

| 4.2 | Introducing New Bison | |||

| 4.3 | Breeding | |||

| 4.4 | Calving | |||

| 4.5 | Weaning Bison | |||

| 4.6 | Identification | |||

| Section 5 Handling | ||||

| 5.1 | Moving and Handling Bison | |||

| 5.2 | Facility Design | |||

| 5.3 | Handling Facilities | |||

| 5.4 | Restraining | |||

| 5.5 | Operations | |||

| 5.6 | Handling Considerations | |||

| 5.6.1 | Preparing the Herd for Processing | |||

| 5.7 | Behavioural Signs of Stressed Bison | |||

| 5.8 | Dehorning | |||

| 5.9 | Tipping | |||

| 5.10 | Branding | |||

| 5.11 | Castration | |||

| Section 6 Transportation | ||||

| 6.1 | Pre-Transport Decision Making and Preparation | |||

| 6.2 | Arranging Transport | |||

| 6.3 | Loading and Receiving | |||

| Section 7 On-Farm Euthanasia | ||||

| 7.1 | Euthanasia Decisions | |||

| 7.2 | Decision-Making Around Euthanasia | |||

| 7.3 | Methods of On-Farm Euthanasia | |||

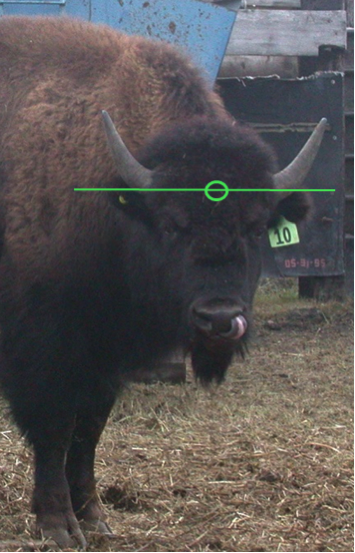

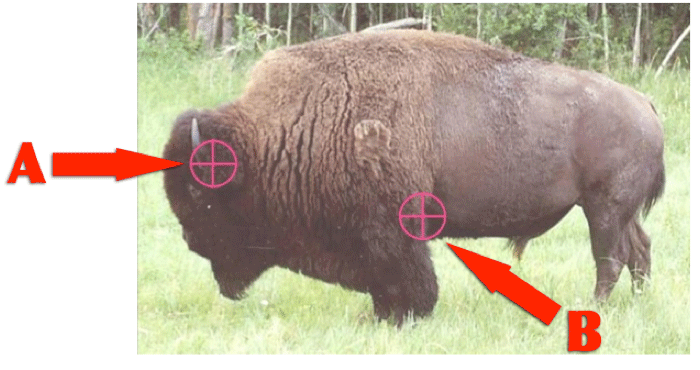

| 7.4 | Shot Placements | |||

| 7.5 | Confirmation of Insensibility and Death | |||

| References | ||||

| Appendices | ||

| Appendix A | - Stocking Rates for Pastures | |

| Appendix B | - Preventing Escaped Bison | |

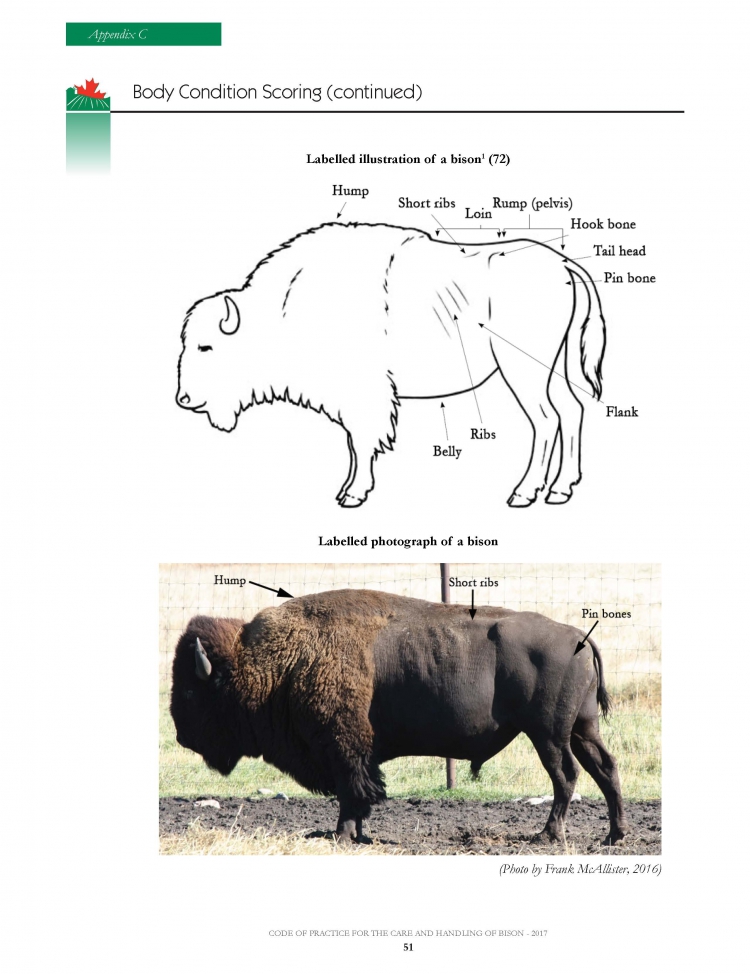

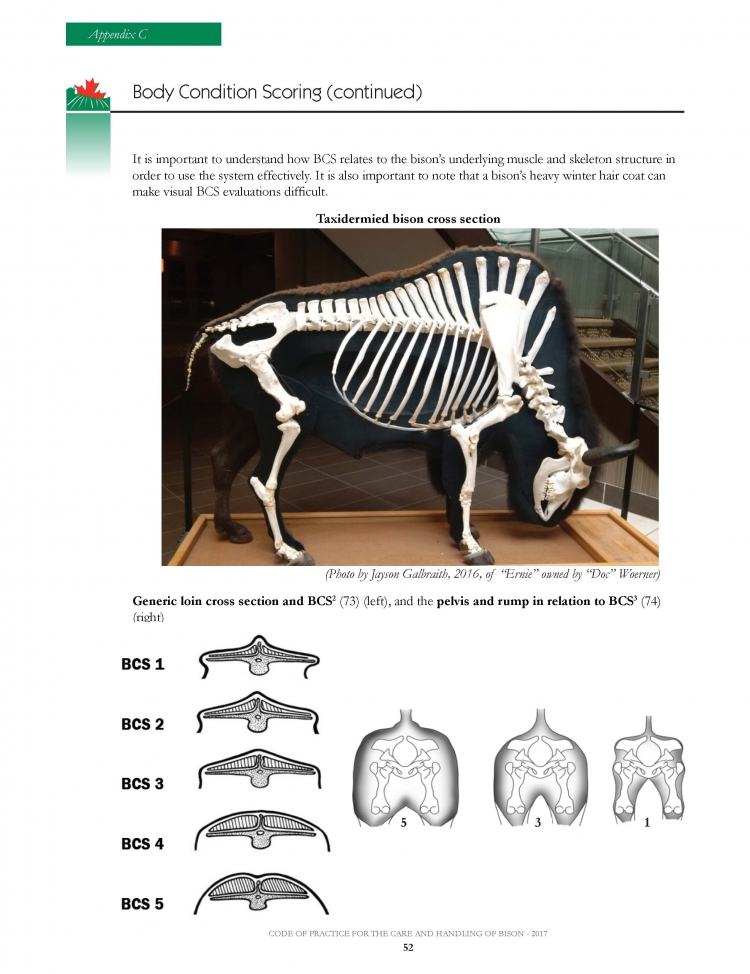

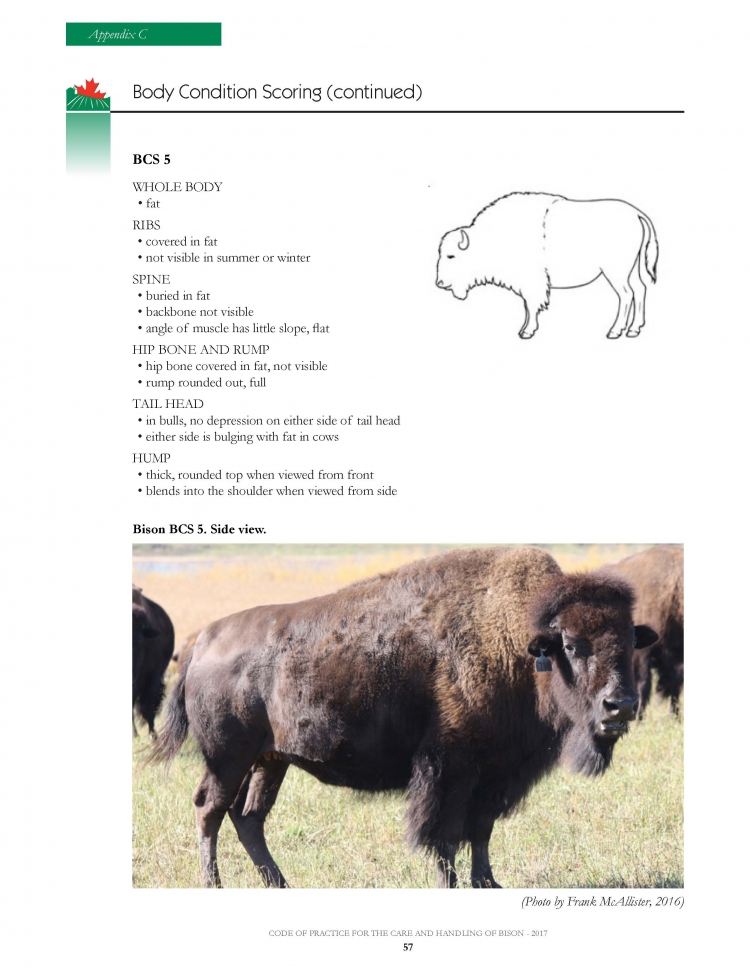

| Appendix C | - Body Condition Scoring | |

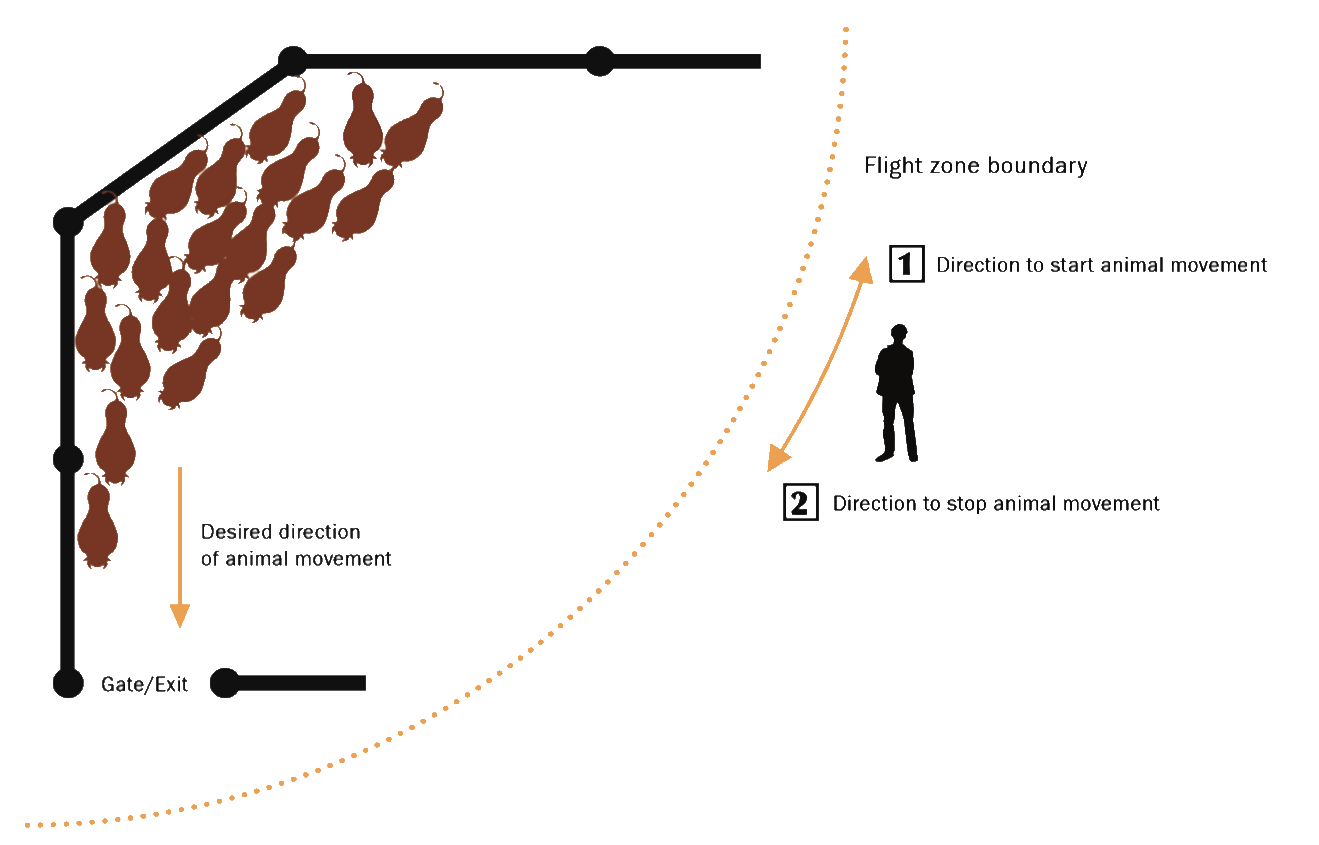

| Appendix D | - Bison Flight Zone | |

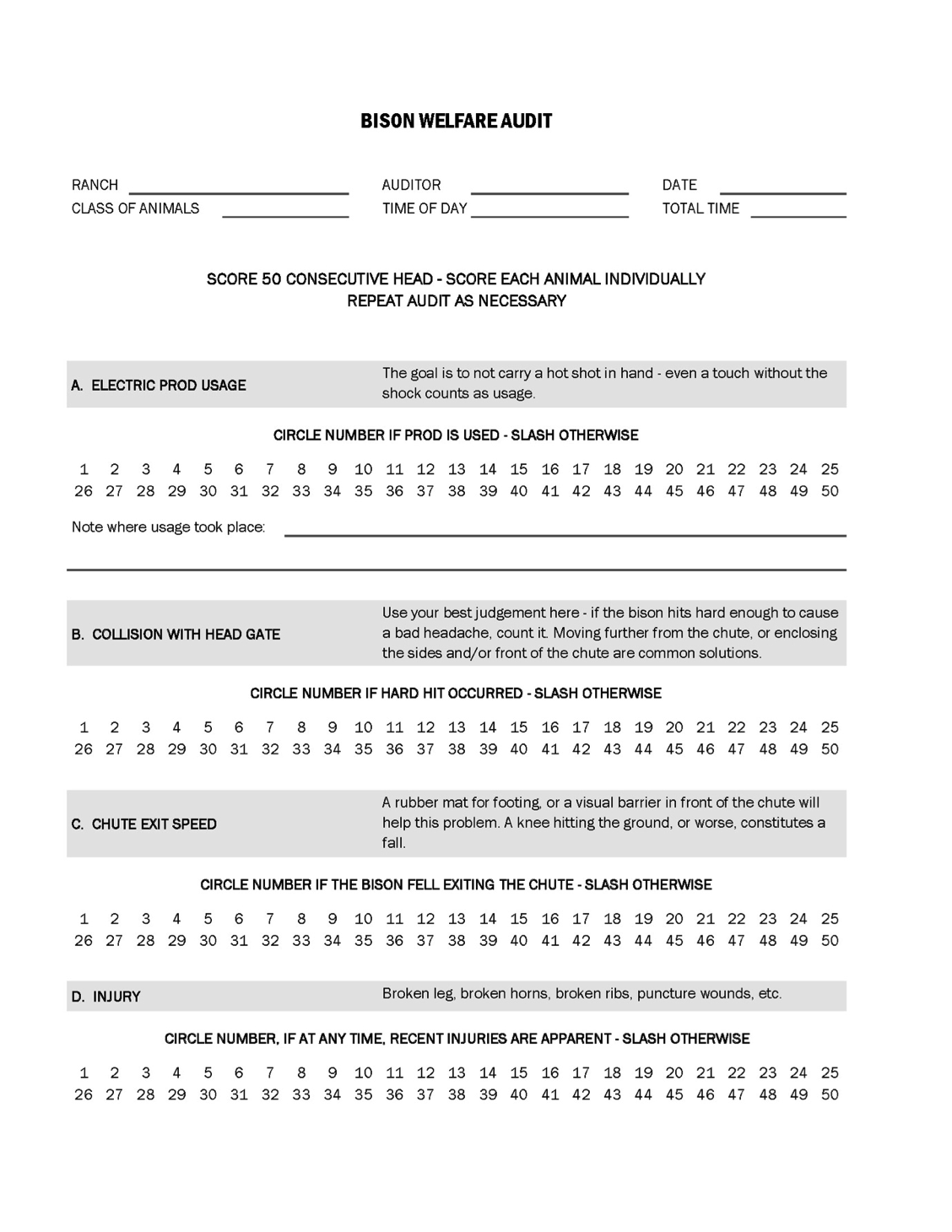

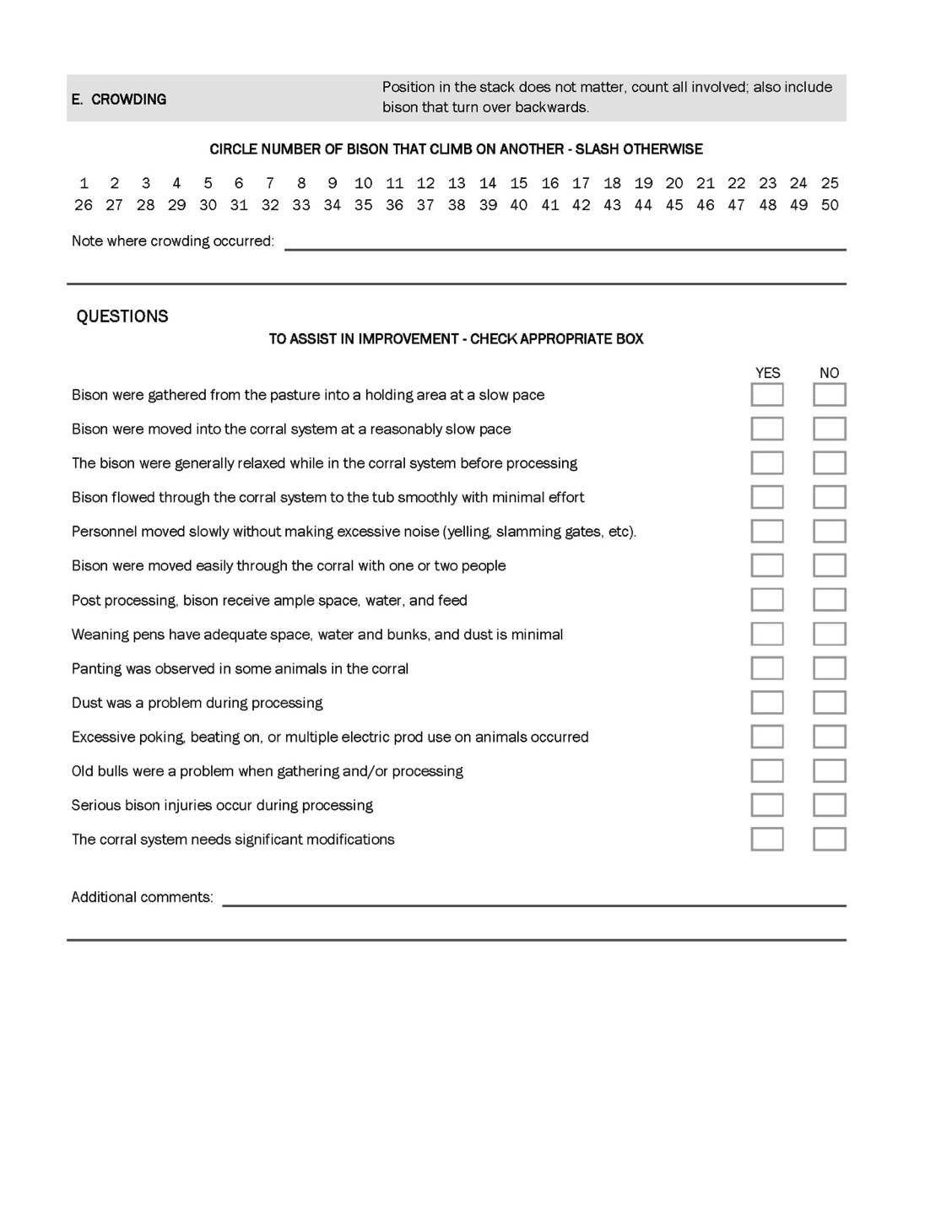

| Appendix E | - Bison Processing Welfare Audit | |

| Appendix F | - Orphaned Calves | |

| Appendix G | - Transport Decision Tree | |

| Appendix H | - Resources for Further Information | |

| Appendix I | - Participants | |

| Appendix J | - Summary of Code Requirements | |

Preface

The National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC) Code development process was followed in the development of this Code of Practice. The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Bison replaces its predecessor developed in 2001 and published by the Canadian Agri-Food Research Council (CARC).

The Codes of Practice are nationally developed guidelines for the care and handling of farm animals. They serve as our national understanding of animal care requirements and recommended practices. Codes promote sound management and welfare practices for housing, care, transportation, and other animal husbandry practices.

Codes of Practice have been developed for virtually all farmed animal species in Canada. NFACC’s website provides access to all currently available Codes (www.nfacc.ca).

The NFACC Code development process aims to:

- link Codes with science

- ensure transparency in the process

- include broad representation from stakeholders

- contribute to improvements in farm animal care

- identify research priorities and encourage work in these priority areas

- write clearly to ensure ease of reading, understanding and implementation

- provide a document that is useful for all stakeholders.

The Codes of Practice are the result of a rigorous Code development process, taking into account the best science available for each species, compiled through an independent peer-reviewed process, along with stakeholder input. The Code development process also takes into account the practical requirements for each species necessary to promote consistent application across Canada and ensure uptake by stakeholders resulting in beneficial animal outcomes. Given their broad use by numerous parties in Canada today, it is important for all to understand how they are intended to be interpreted.

Requirements- These refer to either a regulatory requirement or an industry imposed expectation outlining acceptable and unacceptable practices and are fundamental obligations relating to the care of animals. Requirements represent a consensus position that these measures, at minimum, are to be implemented by all persons responsible for farm animal care. When included as part of an assessment program, those who fail to implement Requirements may be compelled by industry associations to undertake corrective measures or risk a loss of market options. Requirements also may be enforceable under federal and provincial regulation.

Recommended Practices- Code Recommended Practices may complement a Code’s Requirements, promote producer education, and encourage adoption of practices for continual improvement in animal welfare outcomes. Recommended Practices are those that are generally expected to enhance animal welfare outcomes, but failure to implement them does not imply that acceptable standards of animal care are not met.

Broad representation and expertise on each Code Development Committee ensures collaborative Code development. Stakeholder commitment is key to ensure quality animal care standards are established and implemented.

This Code represents a consensus amongst diverse stakeholder groups. Consensus results in a decision that everyone agrees advances animal welfare but does not necessarily imply unanimous endorsement of every aspect of the Code. Codes play a central role in Canada’s farm animal welfare system as part of a process of continual continual improvement. As a result, they need to be reviewed and updated regularly. Codes should be reviewed at least every five years following publication and updated at least every ten years.

A key feature of NFACC’s Code development process is the Scientific Committee. It is widely accepted that animal welfare codes, guidelines, standards, or legislation should take advantage of the best available research. A Scientific Committee review of priority animal welfare issues for the species being addressed provided valuable information to the Code Development Committee in developing this Code of Practice.

The Scientific Committee report is peer reviewed and publicly available, enhancing the transparency and credibility of the Code.

The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Bison: Review of Scientific Research on Priority Issues developed by the Bison Code of Practice Scientific Committee is available on NFACC’s website (www.nfacc.ca).

Introduction

Bison are the largest indigenous, free-ranging ruminant in North America. The historic range of bison included most of western North America from Alaska to Northern Mexico. While tens of millions of animals once roamed the plains, they were hunted to near extinction with approximately 1,000 animals remaining by the late 1800s (1). The species successfully returned from near extinction due to public support and the actions of visionary conservationists, ranchers, and policy makers. Today, bison roam in the wild, within public parks and on private ranches throughout North America. In 2017, it is estimated that there are 380,000 bison living on 3,200 ranches in Canada and the United States. There are also about 30,000 bison living in protected wild spaces. The North American bison recovery is truly a conservation success story (2).

The farming of bison is a relatively new agricultural practice. In Canada, commercial production became increasingly financially viable during the 1980s. While bison meat initially served local markets, production expanded to meet North American and European consumer demands. The commercial bison industry today is well organized, vibrant, and sustainable.

Bison farming in 2017 continues the vision of early ranchers who contributed to preserving the genetics and diversity of the species. Ranchers identified and valued bison attributes that evolved naturally over centuries in response to the North American climate and topography. Early ranchers identified economic benefits that these attributes brought to commercial production. Bison producers have developed the skills required to handle the unique personality and undomesticated spirit of this species. Bison retain a wild nature; managers must respect that nature in currently evolving production systems.

This Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Bison was developed with respect for, and an understanding of, the wild nature of bison. It also reflects available scientific research, both bison-specific and research undertaken in other livestock and wild species.

This Code focuses on the needs and preferences of the animal, where they are known. Where possible, it is outcome-based, and is intended to achieve a workable balance between the best interests of the bison, producers, and consumers. It articulates and encourages the basic principle that safeguarding the natural well-being of bison is of utmost importance. The Code aims to promote scientifically valid and feasible approaches to meeting bison health and welfare needs throughout the production system. The Code supports a sustainable, and largely natural, bison industry.

This Code is not intended to describe all production and management practices relevant to each life stage of farmed bison. Instead, principles applicable to all sectors of the industry are presented along with some sector-specific considerations.

This Code reflects current bison on-farm management practices. It identifies welfare hazards, opportunities, and methods to assure well-being. The bison Code includes important pre-transport considerations but does not address animal care during transport. Consult the current Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals: Transportation for information on animal care during transport.

Bison herds require sorting and handling. Anyone building new, or modifying or assuming the management of existing, bison facilities will need to be familiar with local, provincial, and federal requirements for construction, environmental management, and other areas beyond the scope of this document. Individuals requiring further details should refer to local sources of information such as universities, agricultural ministries, and industry resources (see Appendix H).

This Code represents the standards of care that are required by the animal protection statutes of most provinces and territories. Provincial and federal acts and regulations are also applicable to all livestock production (e.g., Health of Animals Regulations). It is of benefit to the entire Canadian bison industry that the community of bison producers assures bison husbandry is of the highest standard possible.

The Canadian Bison Association will continue to support research and technology transfers to enhance production, management, and conservation practices that benefit both bison and the people who manage them. Continuous improvement in management practices that focus on the welfare needs of the animal will ensure that bison continue to thrive on Canadian farms and further contribute to this conservation success story.

This Code was built on the work of the many individuals who developed the 2001 bison Code of Practice as well as researchers and producers who have freely shared their knowledge, experience, and information over the past 15 years. The Bison Code Development Committee would like to acknowledge the late Dr. Bob Hudson for his work benefiting the farmed bison industry. Bob was an enthusiastic, passionate, and cheerful advocate for ranching native ungulates and contributed significantly to the 2001 Code.

Glossary

Abscess: collection of pus in a cavity or capsule (3).

Alleys/Races: narrow corridors within handling facilities intended to control and direct animal movement from one location to another (4).

Analgesic: a drug that relieves pain in an animal that is not sedated.

Anesthetic: a medication that causes a temporary loss of feeling or sensation. There are two kinds of anesthetic: general and local.

Antibody: a specific protein that is produced in response to the presence of a foreign protein (antigen), usually an infectious agent that has been introduced into the body.

Assembly yards: where animals are assembled for further distribution; usually not open to the public.

Auction markets: livestock buying and selling venues open to the public.

Bison conformation: the shape of a bison, particularly feet, legs and smoothness of motion. Conformation is a strong predictor of longevity in range livestock.

Bison squeeze chute: a specially designed, reinforced steel cage with a head gate and crash gate used to safely restrain bison when necessary (e.g., during ear tagging, administering vaccines or deworming, and while receiving veterinary treatment). Also called bison squeeze or squeeze.

Bloat: abnormal distension of the rumen as a result of accumulated gases that cannot escape (3).

Body condition scoring (BCS): a subjective, 5-point scoring system used to reflect the amount of fat cover on an animal. BCS is an important tool for monitoring feeding programs.

Branding: the act of creating a permanent scar on the skin in the shape of a number or symbol for the purposes of identification.

Breeding heifer: a young female bison of sufficient age and body condition as to likely become pregnant if exposed to fertile bulls.

Bunk feeding: feeding animals concentrated feeds from troughs or containers. Typically seen in finishing yards (i.e., penned areas where concentrate feeds or total mixed rations are fed).

Bunting behaviour: butting or rubbing of the head against another animal or object.

Capture myopathy: a degenerative, often lethal muscle condition that can be brought on by extreme exertion and overheating. In bison, it is most commonly associated with poor handling where animals experience considerable stress and excitement (3).

Castration: surgical procedure of removing the testicles from a male animal.

Catch pens: corrals or paddocks used to sort bison prior to handling or shipping.

Cattle guard : a wide steel grid laid flat over a hole or ditch on a road or path intended to prevent the crossing of livestock. Bison guards need to accommodate specific bison characteristics. Also called Texas gate, cattle grid, stock guard, or guard (3).

Centrefire cartridge: a firearm cartridge in which the primer required to initiate the firing process is contained in the centre of the base (3).

Circle system designs: a handling infrastructure layout involving curved alleys intended to facilitate animal movement through passageways based on natural behavioural inclinations.

Colostrum: the first milk given by a dam after calving. It is high in antibodies that protect the calf from infection.

Commingling of bison: the mixing of animals from different operations or herds (3).

Compromised animal: an animal with a reduced capacity to withstand transportation but where transport with special provisions will not lead to suffering. Compromised animals may be transported directly to the nearest appropriate place to receive care or treatment or to be slaughtered or euthanized (see Appendix G).

Convalescence: the recovery process associated with ill health or injury.

Corneal reflex: the reflex of blinking the eye when the surface of the eyeball (cornea) is touched. The absence of a corneal reflex is associated with insensibility and brain death.

Cross breeding: breeding with another species or variety to create a hybrid animal.

Culled: bison that have been removed from a breeding herd.

Dam: female parent.

Dehorning: the act of removing the horns of an animal (i.e., partial or full) where vascularization and innervation is present.

Downer: an animal that is unable to stand on its own due to injury or disease (3). Also called downed animal (3).

Dystocia: abnormal or difficult birth, resulting in problems delivering a calf (3).

Ectoparasites: parasites that live on the outside of their hosts (3).

Electric prod: hand-held tool with electrodes on the end designed to cause pain in animals through a relatively high-voltage, low-current electric shock. Livestock move away from the source of pain. Also called hot shot (3).

Electrolyte nutritional therapy: nutritional supplements fed to livestock prior to transport that are intended to reduce transport stress.

Emaciation: a state in which an animal is severely thin (usually associated with starvation or illness).

Energy sparing cycle: behavioural and physiological adaptations observed in many wild ruminants of temperate and arctic regions. An adaptive response to food scarcity that enhances survival in harsh environments. During these periods, feed intake, and consequently growth, is restricted. Also called seasonal variation or nutritional seasonality.

Esophageal feeder: a device that allows for the safe delivery of milk directly into a newborn animal’s stomach (i.e., via the esophagus). Also called stomach tube or tube feeder.

Euthanasia: the humane killing of an animal.

Exsanguination: a secondary kill step intended to ensure that an animal dies promptly following humane stunning. A reference to allowing the majority of an animal’s blood to leave the body through a deliberate wound; usually the severing of the major blood vessels of the neck. Also called bleeding out.

Extra-label: a non-approved use of medication (e.g., using cattle vaccine on bison). A medication label can only contain information approved by government regulators and includes the approved species, the dosage, the conditions treated, and the drug withdrawal time in food animal species. A veterinarian can prescribe specific use in a species, dose, or condition not included in the label where the drug has a high probability of successful treatment. Drug manufacturers are not liable for extra-label use of products.

Fecal testing: the analysis of stool samples usually for the presence of parasite eggs or other infectious causes of intestinal diseases.

Feed concentrates: feed source derived primarily from starch (grain) as opposed to cellulose(e.g., stems and leaves of grasses) in free choice feeding.

Fit animal: an animal that is considered capable of enduring the stress of a planned journey and that can be transported without suffering.

Flight zone: the distance between an animal and a perceived threat (such as a human) at which the animal will move away. In bison, this distance is much greater than in other livestock species.

Forage: edible cellulose-based plant material such as grass, hay, greenfeed, silage (i.e., fodder).

Free choice: a feeding scenario in which livestock are provided constant access to feeds of varying quality or nutritional content in order to allow animals to balance their diets as preferred (3).

High energy feeding: a feeding regimen that relies on a nutritionally-balanced ration with a high proportion of processed grains, premixes, and supplements and a low proportion of forages such as hay or silage. Such diets are typically used to finish animals prior to slaughter.

Horn cap: the exterior cuticle or covering of a bison horn.

Humane: describing human behaviour, activities or character marked by feelings of kinship, compassion, sympathy, or consideration for humans or animals. A human virtue in relation to human-animal interactions characterized by respect, kindness, attention to, and obligation for animal welfare.

Husbandry: the care and management of farmed animals (3).

Innervated: an organ or body part supplied with nerves (3).

Insensible: unconscious and unable to perceive pain.

Interspecies dominance: social hierarchy across species such as cattle and bison.

Joules: a unit of energy equal to the work done by a force of one newton (i.e., a basic unit of force) acting through a distance of one metre (3).

Maternal antibodies: antibodies passed from the mother to her offspring (i.e., after birth via the colostrum).

Micronutrient: a component of the diet (typically a chemical element) required in very small amounts for normal growth and development (3).

Natural: a reference to wholeness or completeness of an animal and the capacity to maintain itself independently in an environment suitable to the species (5).

Non-ambulatory: being unable to stand or walk without assistance or a situation where an animal is not bearing any weight on one leg (3).

Non-breeding/Feeder animals: individual animals and groups selected for meat production as opposed to reproductive purposes.

Nose tongs: a temporary restraint device applied to the nose of a bison during handling to limit head movement. Domestic cattle react negatively to the use of nose tongs (6,7).

Outcome-based: an approach to evaluating animal welfare based on the observable state of the animal at a point in time. Evaluating animal welfare by focusing on body condition scoring, morbidity, and mortality rates: things that can be measured or scored fairly. Frequently contrasted with “engineering-based” focus, in which welfare is assessed by evaluating the physical environment such as the construction method and height of a fence or the specific width of a runway.

Palpating a cow: physically examining a cow for pregnancy by trans-rectal (i.e., through the rectum) evaluation of the uterus. Pregnancy can also be determined by trans-rectal ultrasound devices.

Parasite: an organism that lives in or on another organism (i.e., its host) and benefits by deriving nutrients at the host's expense (3).

Parasite load: an estimate of the number and severity or harmfulness of parasites that a host organism harbours (3).

Parasitism (internal): a situation of close, long term association between two organisms where one benefits to the detriment of the other.

Passive immunity: the acquisition of immunity from a donor animal (e.g., via a dam’s colostrum).

Pesticide: a chemical substance used to kill harmful insects, wild plants and other unwanted organisms in the environment.

Portable panels: lightweight fencing, frequently made of tubular metal, used to contain or direct bison during handling operations.

Post-mortem: a medical examination of a dead animal to determine cause of death (3).

Preconditioning: the practice of introducing a calf to vaccination, weaning, and a feed regimen prior to sale or to the next step in a producer’s feeding program.

Production cycle: the annual cycle of events required for the profitable operation of a livestock farm. The successful reproductive cycle in breeding herds and the growing-out period for slaughter bison.

Prolapse: a condition where organs (e.g., the uterus) drop down or slip out of place. This includes organs protruding through the vagina or rectum (3).

Rimfire cartridge: a firearm cartridge in which the primer required to initiate the firing process is contained in a rim surrounding the base (3).

Rumen function: the breaking down of plant fibres into smaller digestible elements within a rumen (i.e., the largest portion of a ruminant’s four-sectioned stomach). Proper rumen function is dependent on a healthy and active microbial population within the stomach (3).

Ruminant: a hoofed mammal that regurgitates and re-chews food initially stored in its rumen (i.e., the largest portion of a ruminant’s four-sectioned stomach).

Rumination: the act or process of chewing cud (3).

Rutting period: the mating season of ruminants.

Staging bison: gathering bison for loading onto a vehicle.

Stocking rate: the number of specific types and classes of bison that can graze a unit of land for a specific time period. It is usually classified as the number of animal units an acre of land can hold for one month (AUM/acre).[i]

Stray voltage: the presence of low levels of electrical current in the metalwork of farm buildings and equipment such as watering devices. Usually a result of poor wiring or improper grounding of the electrical system. Can result, for example, in bison receiving shocks when drinking. Also called tingle.

Supplement: an addition to a livestock ration intended to make up for any nutritional deficiencies associated with other/basic feedstuffs (3).

Supplementary feeding areas: typically non-pasture, penned areas where bison are fed stored feeds in the weeks prior to slaughter or where bison are loosely held for ease of overwinter feeding.

Thermoregulation: the ability of an animal to maintain its core body temperature independently of its immediate surroundings (3).

Tipping: the act of removing the end of an animal’s horn (no innervation or vascularization present, and no bleeding as a result) in order to reduce the severity of goring or other injuries.

Trace mineral: a mineral component of the diet required in small amounts to support normal growth and development.

Tub: a circular component of a handling system where bison movement is transitioned from wide alleys into narrower, working alleys.

Unfit animal: an animal that cannot be transported without suffering. Unfit animals may only be transported for veterinary diagnosis or care (see Appendix G).

Ungulate: a hoofed mammal.

Vascularized: tissue or structure containing (blood) vessels (3).

Wallowing: an active behaviour of bison consisting of rolling about or lying relaxed in water, mud, or sand (3).

Weaning: the separating of calves from their mothers and the removal of milk as a food source.

Weaning (fence line): separation of the cow and calf to opposite sides of a fence, thereby having visual and auditory contact. Not recommended for bison.

Weaning(two-stage): calves initially remain with their dams, but wear a nose-flap to prevent nursing for 5-7 days. The nose flaps are then removed and the cow-calf pairs are separated. Not recommended for bison.

Yearling: a bison between one and two years of age.

Section 1 Animal Environment

Desired Outcome: Bison are kept under conditions conducive to good nourishment, health, safety, and humane handling.

1.1 Grazing Environment

Recommended stocking rates vary with the area of the country (see Appendix A). It is important that mineral supplementation be balanced with any deficiencies in the area.Monitoring the prevalence of parasites in the herd through observation and regular fecal testing should provide signs of parasitic load and be appropriately treated. Since most, if not all, products used for the treatment of parasites in bison are extra-label, producers should consult a veterinarian on the appropriate products, dosages, and withdrawal times.

1.2 Pasture Management

Pasture management impacts bison health. Pasture-based finishing may be more amenable to bison well-being than confined feeding and handling. Hence, grazing planning and management supports responsible animal care (8). Native rangeland and seeded pastures, including alfalfa, are suitable for bison. Pastures with a mix of habitat types provide foraging that extends the grazing season.

REQUIREMENTSBison on pastures must be monitored to ensure sufficient quality and quantity of feed, minerals, and water (see Section 2 – Feed and Water) |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide bison on pasture or range with well-drained resting areas.

1.3 Supplementary Feeding Areas

Supplementary feeding areas are often used to hold bison temporarily for wintering, calving, or finishing. Because bison tend to be more active than other species, feeder pens should allow for sufficient space. Larger, older animals will require more room.

REQUIREMENTSSupplementary feeding areas must provide unrestricted access to clean, fresh drinking water. Bison must be able to move freely around the feeding area and have adequate amounts of forage or feed continuously available to eliminate feed competition (10). Feed and water must be distributed in such a way that bison can eat and drink without excessive competition. A dry or elevated resting area must be available at all times. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- calculate space allowances for bison in feed areas in relation to group size as well as animal age, sex, and weight

- avoid mixing species in feeding areas because of interspecies dominance or aggressive interactions

- ensure that feeder pens allow for a minimum of 23 square metres (250 square feet) per head

- provide a minimum bunk space of 1 metre (3 feet) per animal if bunk feeding is being used.

1.4 Fencing

Secure fencing is essential to containing bison. Bison are unlikely to challenge fencing if they have sufficient grass, minerals, water, and room to evade more dominant animals.

No single fence design is suitable for all landscapes, site conditions, or containment requirements (11). Hence, fencing should be designed to meet or facilitate the unique needs of individual operations (while accommodating provincial regulations regarding acceptable fencing provisions or practices). It is the responsibility of those overseeing the care of bison to ensure containment.

Fencing should be built with the topography of the land in mind. Upward slopes can enhance the effective height of a fence. Fallen limbs, vegetation cover, or packed snow may compromise effective fence heights (11).

REQUIREMENTSPerimeter fences must be well constructed and regularly maintained. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide 2 m (six-foot) perimeter fencing

- fence water courses, as bison are good swimmers. Water is an ineffective barrier to bison movement

- inspect all fences regularly (and repair if necessary). Additional inspections may be necessary immediately after a wind storm, snow blizzard, heavy blowing snow, or after escaped animals have returned

- ensure that all perimeter gates have secure latches and locks if necessary

- consult industry and association publications about current best practices regarding fencing materials

- use double-width cattle guards, or “Texas gates,” to contain bison. Allow room for packed snow in pits underneath (11).

1.5 Environmental Management

Bison have a natural ability to withstand most extreme weather conditions. Bison living outside of their traditional habitats, however, may require additional provisions (e.g., in regions with mild, rainy, and muddy winters). It is always important to monitor animals and to respond when necessary.

Bison are generally able to tolerate low temperatures better than high temperatures. Extreme heat is typically more stressful to bison in early summer before they have acclimated to increased temperatures.

Handling bison on a hot day may lead to heat stress.

REQUIREMENTSProducers must be prepared to assist animals not coping with their environment. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- avoid handling bison in temperatures exceeding 30˚C (86˚F)

- ensure that a plan is in place to assist animals not coping with their environment.

1.6 Safety and Emergencies

Emergencies may arise and compromise bison welfare. Pre-planning will assist in both avoiding and responding to such events.

REQUIREMENTSSteps must be taken to prevent exposure of bison to toxic or potentially dangerous materials (e.g., chemical storage facilities). All fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides must be applied so as to minimize risks to grazing animals. Follow label instructions regarding grazing restrictions. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- prepare contingency plans for risks such as grass fires, severe storms, vandalism, drought, damaged fences, and water source failures

- remove mechanical hazards such as farm machinery and scrap metal from areas accessible to bison

- monitor pastures during the grazing period for poisonous plants. Producers should be knowledgeable of poisonous species in their region

- exclude bison from dugouts and/or natural water bodies during periods when ice is not thick enough to be considered safe.

Section 2 Feed and Water

Desired Outcome: Bison experience freedom from hunger, thirst, and malnutrition. Bison have ready access to fresh water and a diet designed to maintain full health and promote a positive state of well-being.

2.1 Nutrition and Feed Management

Well-fed bison will maintain body condition and optimize growth and reproduction. Knowledge of nutritional needs of bison is largely extrapolated from beef cattle and verified by producer experience. Good quality forage (hay or pasture) should form the bulk of the diet for breeding bison. A herd of breeding bison can flourish on pasture and overwinter on good quality forage alone.

A normal winter weight loss of 10–15% of pre-winter body weight is expected in adult bison due to daylight related changes in the metabolic rate (12). In spring and summer, bison greatly increase foraging time and decrease resting time. Under sedentary winter conditions, bison decrease their voluntary feed intake (13,14,15). Bison should be managed nutritionally to maximize the natural annual energy sparing cycle of this species (16,17).

When feeding free choice grain or pellets with good quality forage, bison will not eat grain to the exclusion of roughage (18,19,20).

Body condition scoring (BCS) is an important tool for determining if an adult animal is too thin (BCS of less than 2 out of 5), too fat (BCS greater than 4 out of 5), or in ideal condition (see Appendix C). Ideal body condition scores will vary depending upon season and class of animal (see Table 2.1). Body condition scoring targets also allow producers to optimize the use of feed resources and animal productivity. Within a group of similar age and type, the differences in BCS between individuals should be minimal.

Table 2.1 - Seasonal body condition score targets for breeding herds1

Class | August | September | January | May |

Breeding Cows | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 |

Breeding Heifers >2 yr2 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 |

Bulls | 3/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 |

Replacement Breeding Heifers <2 yr2 | 3/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 |

Yearlings 1-2yr | 3/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | 3/5 |

Older Cows >18 yr3 | 2.5/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 | 2/5 |

1Individual variation in body condition is expected in any population; the target scores are intended to reflect the group average. 2As of May. 3Older cows should be monitored closely and if they drop to a BCS of 1.5 should be culled from the herd before they risk becoming compromised (see Section 6 – Transportation). 4 (21). | ||||

Micronutrient supplements should be provided where there are specific deficiencies in regions’ soil and feed quality. Nutritional mineral deficiency results in low conception rates, weak calves, increased morbidity and mortality, and increased parasite load (22). Common deficiencies include iodine, copper, and selenium and vitamin E. A balance of calcium and phosphorous is also required in the diet. Trace mineral can be provided in pressed blocks that are primarily salt. Free flowing (bagged) trace mineral-salt supplement is also available.

Table 2.2 - Indication of trace mineral supplementation of salt blocks by colour

Colour | Trace Mineral Fortification |

White | Sodium Chloride (NaCl) or table salt |

Red | NaCl, iron and iodine |

Blue | NaCl, cobalt and iodine |

Brown | NaCl, cobalt, iodine, iron, zinc, copper, molybdenum, manganese |

Black | NaCl, cobalt, iodine, iron, zinc, copper, molybdenum, manganese, selenium |

This colour scheme is an industry convention; refer to the manufacturers’ label claim on the specific blocks of salt for actual content. Some brown product may also contain potassium and magnesium. The blue cobalt block was created for the deficiencies found in northwest British Columbia and northern Alberta (23). | |

REQUIREMENTSBison must have access to feed of adequate quality and quantity to:

Prompt corrective action must be taken to improve the body condition score of individuals with a BCS of less than 2 out of 5. Bison on pasture must have access to free choice fortified salt, choice trace mineral, and access to good quality pasture. Bison diets must contain forage to ensure proper rumen function. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- evaluate pasture conditions in accordance with seasonal and annual variations in pasture production

- store feed in an appropriate manner to prevent growth of moulds and contamination from rodents, birds, and insects. Feed quality, particularly vitamin activity, will deteriorate during storage. Manufacturers' expiration dates on feed supplements should be respected

- become familiar with potential micronutrient deficiencies or excesses in your geographic area and use appropriately-formulated supplements

- provide sufficient feed to enable adult bison to gain 10–15% body weight (1 BCS) from May to December. Allow bison to lose that gain from December to May

- provide sufficient feed to calves of the year to enable them to continue to grow and maintain body weight over the winter feeding period

- monitor older cows, young cows, and heifers to ensure they are gaining anticipatory body weight in the autumn. Replacement heifers born late in the previous season may benefit from segregation and supplemental feeding in the fall (i.e., optimum metabolic period)

- remove twine and net wraps from baled forage prior to feeding (24).

2.2 Water

Bison need access to water of adequate quality and quantity to fulfil their physiological needs. Water availability and water quality are extremely important for bison health and productivity. The average daily requirement for an animal weighing 500 kg (1100 lbs) is approximately 45 L (10 gal) per animal (6–12% of body weight), varying with dry matter intake and environmental temperature (25). All animals shall either have access to a suitable water supply and be provided with an adequate supply of fresh drinking water each day or be able to satisfy their fluid intake needs by other means.

Water sources can include wells, natural streams and ponds, or abundant clean loose snow in extensive grazing systems. Care should be taken to provide water after fall frosts, unless snow is available, and where snow cover is inadequate.

Where well water is the primary source, water sample analysis can identify minerals and metals that can interfere with the bioavailability of trace minerals.

Water quality (i.e., palatability) affects water consumption. Bison will limit their water intake if the quality of drinking water is compromised (e.g., polluted by algae, manure, or urine).

REQUIREMENTSBison must have access to an adequate and clean source of water at all times. Producers must monitor water sources and snow conditions on an ongoing basis and be prepared to adjust their watering programs accordingly. Producers must have a backup water source available in the event of insufficient loose snow or an interruption in regular water supply. Snow must not be used as a sole winter water source unless it is of sufficient quantity and quality to meet the animals’ physiological requirements and the body condition score of individuals remains greater than 2. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- manage bison and water sources to prevent competition and excessive wet or muddy areas

- check and clean automated water sources regularly to ensure water systems are dispensing properly

- test water quality in the event of problems such as poor performance, reluctance to drink, or reduced feed consumption

- provide water in troughs or bowls wherever possible if utilizing natural water sources to ensure cleanliness of the water supply and safe animal access

- provide an area of open water and restrict bison from areas of thin ice, as frozen-over natural water sources in winter are a physical hazard to bison

- watch for signs of stray (tingle) voltage from mechanical winter water sources, such as reluctance to drink or reduced feed consumption, and take corrective action

- evaluate well water for mineral content if used as the exclusive water source for bison.

Section 3 Animal Health

Desired Outcome: Optimum health and welfare are maintained through a proactive approach to disease prevention, control measures, and the prompt treatment of illness, injury, and disease.

3.1 Health Management

While bison are typically robust animals with strong immune systems, they may be afflicted by major diseases. Bison health may also be compromised through stress. Stress may arise in relation to environment, management, handling, and other sources (26). Pain and discomfort caused by health issues impact an animal’s well-being (27).

Bison are susceptible to, and can become ill from, many diseases affecting bovine species. As a preventative step, and if manageable, new arrivals may be segregated for a minimum of two weeks. If bison do become ill, it is important that producers employ the necessary means, including seeking professional help, to identify the disease and implement a treatment protocol to reduce pain and suffering.

Bison may also be subjected, and even succumb, to internal parasites. Disease prevention is extremely important for bison, since treating bison once they are sick can be more difficult than in other species. Producers need to be able to recognize and treat health issues promptly in order to optimize animal well-being.

Veterinarians can play a key role in helping producers meet these animal health obligations. At the same time, bison producers frequently operate in remote areas where available veterinary services are limited. Veterinarians rarely specialize in bison production and health.

As a result, it is imperative that bison producers routinely monitor the health of their animals and promptly contact qualified veterinarians when needed. It is possible that initial consultations may require phone conversations with veterinarians from other regions, provinces, or countries. Relying on the help and knowledge of other trained professionals or experienced bison producers may also be necessary. Note that most, if not all, drugs used in bison production are extra-label and require a veterinary prescription for use (28).

Adopting a proactive, anticipatory approach to animal health will ultimately serve the best interests of the herd.

REQUIREMENTSStrategies for parasite control and disease prevention must be developed and implemented. A licensed practicing veterinarian must be consulted when needed. The welfare of bison must not suffer for lack of professional consultation regarding necessary actions pertaining to herd health, nutrition, handling, or facility design. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- develop a biosecurity strategy to prevent disease transmission when introducing new animals into the herd.

3.2 Sick, Injured, and Compromised Bison

The humane treatment of sick, injured, gored, and compromised animals is a priority. Of special concern are downers (non-ambulatory animals) or severely debilitated animals. Prompt decision-making and action are vital to ensure the welfare of these animals.

More frequent monitoring of bison may be necessary during calving and post-weaning periods, and when multiple stressors occur simultaneously (e.g., weaning, transportation, commingling).

Adequate monitoring ensures timely detection and treatment of sick or injured bison. Treatment may vary from therapeutic interventions to convalescent care. Some examples of convalescent care include, but are not limited to, segregation, easier access to feed and water, reduced competition, and increased monitoring.

Signs of illness may be extremely subtle (e.g., high temperature). They may also include spending more time at water sources, drooping ears, mouth breathing, and spending time away from the herd (e.g., lagging behind) (29).

Be aware that bison may hide their expression of pain or suffering and that this may affect your assessment of their condition in making timely decisions about treatment or euthanasia(30).

Bison owners, veterinarians, and laboratories are required to immediately report an animal that is infected—or suspected of being infected—with a reportable disease to a Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) District Veterinarian. Reportable diseases are listed in the Health of Animals Act (available at: inspection.gc.ca/animals/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/eng/1303768471142/1303768544412) and are of significant importance to human or animal health or to the Canadian economy.

Notifiable diseases must be reported to provincial authorities.

REQUIREMENTSBison health must be monitored on an ongoing basis to ensure prompt treatment or care. A veterinarian must be consulted to address new, unknown, or suspicious illness or death losses. A veterinarian must be consulted if the incidence of a known illness suddenly increases. Contagious animals must be segregated and cared for separately from the herd. Care, convalescence, or treatment for sick, injured, or gored bison must be provided without delay. Responses to therapy or care must be monitored. If initial treatment protocol fails, then treatment options are to be reassessed, veterinary advice is to be sought, or the animal is to be euthanized. Records must be kept of treatments, medications, or vaccinations used on all animals. Bison must be euthanized without delay when they (see Section 7 – On-Farm Euthanasia):

Note: Disposal of the carcass must meet local requirements and regulations. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- conduct post-mortems on bison to determine causes of unexpected death.

3.3 Health Conditions Related to Finishing

Disease, parasites, and injuries are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the finishing industry. Supplementary feeding area (SFA) operators should implement appropriate monitoring and oversight to detect disease processes early.

Some risk factors for disease susceptibility are:

- non-vaccinated bison

- recent weaning

- transportation and handling

- sudden or extreme changes in weather

- commingling of bison from various sources

- sudden feed changes

- concurrent diseases such as parasitism.

Early detection and prompt treatment of disease can decrease chronicity and mortality (31).

REQUIREMENTSThe behaviour of bison must be monitored to facilitate the early detection of illness or animal incompatibility. A disease prevention and parasite control strategy must be implemented for new arrivals. A licensed practicing veterinarian must be consulted when needed. The welfare of bison must not suffer for lack of professional consultation regarding necessary actions pertaining to herd health, nutrition, handling, or facility design. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- develop and implement a biosecurity program, which may consist of:

- categorizing newly-arrived bison according to risk for respiratory disease and other illness, and applying appropriate receiving protocols (31)

- buying animals of known sources and health status (31).

3.4 Nutritional Disorders Associated with High Energy Feeding

Bison, like other ruminants, naturally eat a forage-based diet. Grain diets provide extra energy and are used when finishing bison. Grain should be introduced gradually to prevent ruminal acidosis, also known as grain overload. Grain may also be used to bait bison into handling facilities or to deliver medications such as dewormers.

REQUIREMENTSFeeding programs must be designed, implemented, evaluated, and adjusted to facilitate rumination and to prevent the risk of nutrition-induced disorders. Consult your nutritionist or veterinarian when needed. Bison diets must contain forage to ensure proper rumen function. The transition from a high forage to a high energy ration must be done gradually. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- monitor feed stations to assess consumption, and adjust feeding accordingly (31)

- consider adjusting rations to prevent digestive disorders when switching the nutritional source of the feed (31).

Section 4 Herd Management

Desired Outcome: To maximize bison well-being by incorporating their natural attributes into herd management strategies.

Bison are indigenous to North America. They have evolved to survive in the Canadian climate and landscape. It is essential that attributes that have evolved over centuries be considered in bison management (e.g., calving ease, time of calving, strong immune systems, and a dense hair coat that negates the need for artificial shelters in many management systems) (14,15,32,33). Bison have wallowing habits. Wallows are important for grooming and parasite control.Wallowing and rubbing practices are likely related to shedding, male-to-male interactions (typically rutting behaviour), social behaviour for group cohesion, play, relief from skin irritation due to biting insects, the reduction of ectoparasites (ticks and lice), and thermoregulation (34,35,36).

Proper herd management begins with a suitable environment, which is needed to achieve a practical balance between the interests of bison, producers, and society. It is necessary that bison be provided with sufficient space, safety (through secure fencing and suitable handling facilities), and access to sufficient feed, water, minerals, and care to support their health and well-being.

It is imperative that everyone working with bison understand bison behaviour and the importance of social structure within a herd. Bison retain their wild nature. Hence, producers need to have access to handling facilities that ensure the safety of all animals and handlers.

4.1 Management Responsibilities

It is essential that managers outline who is responsible for bison care at every stage of the production cycle. It is also necessary that everyone working with or managing bison understands and accepts their responsibilities for the welfare of all animals under their supervision.

REQUIREMENTSPersonnel must be familiar with normal bison behaviour and be able to recognize indicators of aggression and poor health and welfare so that problems may be identified and addressed as early as possible. Personnel must be knowledgeable about the basic nutritional needs of bison under their care according to gender and age. People caring for bison must have the resources for, and knowledge of, the care and handling practices stipulated in this Code and must ensure that such care is provided. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- monitor staff so that they understand and follow the operational handling procedures, and take necessary corrective actions as required.

4.2 Introducing New Bison

Give careful consideration when introducing new animals into a herd. The way in which bison are introduced to a new ranch or pasture may influence their adjustment process. Social dynamics are important considerations when adding new animals to a herd (37). The goal is always to minimize disruption. Evidence of stress may be indicated by poor performance.

It is always important to minimize competition or fighting in order to reduce injuries. When adding bulls to an existing herd, consideration should be given to adding younger bulls to avoid excessive fighting.

Adding a cow to a herd can be problematic, especially in a small herd. Whenever possible, new female entrants should be introduced in multiples rather than individually.

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- introduce animals of comparable sizes into existing pens of animals

- provide newly introduced animals with space to escape conflict within the social structure

- place younger animals in a pen with a few animals from the larger herd for one day prior to introducing/reintroducing them all as a group

- maintain new arrivals on a familiar feed regimen before slowly transitioning to different feed to reduce stress associated with a new feed source

- monitor animals to confirm feed consumption.

4.3 Breeding

Bison cows are bred naturally. In their natural environment, bison breed when they are two years old and produce their first calves at three. To prevent calving difficulties (dystocia) and other health problems, the timing of the first breeding should take into consideration the overall physical development of the heifer. Cows and heifers should be managed so that they are in a suitable condition at the time of breeding and calving. While conception rates are generally improved by good nutrition, cows are expected to lose 10–15% of their body weight during winter months (leaving cows calving in May relatively lean). Producers have observed that overfeeding cows (using concentrates) may contribute to calving difficulties. The optimal age of breeding bulls is 2–8 years. In multiple sire systems, bulls should be accustomed to one another before joining the cows. Note that crossbreeding between cattle and bison is actively opposed by the bison industry.

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- breeding of bison heifers should occur at two years of age (for calving at three)

- manage the cow herd so that the body condition score is 2–3 during calving season.

4.4 Calving

Bison cows calve in April to late June. Bison normally calve for the first time at three years of age. With proper nutrition, bison cows will calve annually and usually without assistance.

Although there are reports of cows being productive for over 20 years, the average productive life of most bison cows is probably less than 15 years. Under Canada’s climatic conditions, bison calve without the use of shelters. Calving without shelters is consistent with the evolutionary history of bison and is the preferred approach to minimize stress for cows while calving.

While dystocia is very rare in bison, there are few practical options for intervention. Euthanasia is often the best option. It is imperative that those approaching a calving cow or newborn be fully aware of the considerable dangers. Bison cows are very protective of their calves and may not hesitate to attack any perceived threat.

Occasionally, orphan calves will occur in a herd as a result of twinning, or they may be abandoned by their mothers. If left alone, abandoned calves will likely die of starvation. Strategies are available to increase the survival rate of orphaned bison calves (see Appendix F).

REQUIREMENTSProducers must be able to recognize and deal with distressed cows or calves and, if there are no suitable intervention or treatment options, ensure that bison are euthanized to avoid further suffering. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide bison cows with access to clean, spacious pastures that will allow them to move away from the herd to calve when needed

- provide bison cows with access to high/dry ground for the comfort of the cow and calf during wet weather

- confirm that personnel are familiar with procedures to address welfare concerns in the event of calving problems.

4.5 Weaning Bison

Bison are herd animals that maintain a strong social structure. Weaning can be a very stressful time for both calves and cows. Traditional weaning involves removing all calves at one time, placing them in a pen out of sight (and out of hearing range) from the cows, and then allowing them to settle over a few days. This is a recommended process, as the apparent stress of weaning eases after approximately three days. It is also beneficial to introduce older bison surrogates to maintain a level of calmness among the calves when weaning.

REQUIREMENTSWeaned calves must have access to fresh water, mineral, and feed. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- wean calves at six months of age or older

- consider preconditioning calves prior to sale at an auction facility

- avoid fence line and two-stage weaning, due to the nature of bison.

4.6 Identification

All bison are to be identified with an approved bison tag when they leave their farm of origin (unless they are being transported to a designated tagging site where they are tagged by the tagging site operator with the approved tags that have been issued to the owner of the farm of origin).

REQUIREMENTSAll bison must be identified using an approved tag for bison as stipulated by applicable federal regulations. Tags or identification devices must be applied as recommended by the manufacturer. Branding bison for herd identification purposes must not be practiced. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- use visual herd management tags to facilitate individual bison management within a herd

- maintain all identification equipment in working order.

Section 5 Handling

Desired Outcome: For bison to experience minimal stress, discomfort, or injury during handling while necessary husbandry tasks are conducted properly, safely, and efficiently.

5.1 Moving and Handling Bison

Bison can be handled safely without injuries or death loss. This can be achieved with functional facilities and experienced handlers. Continuous improvement can be measured using an audit (see Appendix E). Bison should always be handled with care in a patient and relaxed manner. There is less risk of injury to both animals and humans when bison are handled calmly and quietly. Bison with a history of gentle handling will also be easier to handle in the future (38,39). Experienced handlers who are aware of bison behaviour (including herd instinct, flight zone responses, natural reactions to novel experiences, and susceptibility to fatal stress/capture myopathy) will be able to move bison more smoothly (see Appendix D). This will also decrease stress and promote bison welfare.

While it is important that handlers work without delay once animals are restrained during processing, it is equally important that bison not be hurried or pushed forward too quickly beforehand. Animals that become stressed during the lead-up to restraint are more likely to injure themselves or others and/or balk.

Habituating bison to handling areas (40) by providing water in catch pens, for example, may help to reduce stress during round up. Driving out to herds and providing small amounts of grain weekly will make bison quieter around vehicles and easier to bait into handling areas, if necessary.

REQUIREMENTSAnimal handlers must be familiar with normal bison behaviour (through training, experience, or mentorship) and use quiet handling techniques. Electric prods must only be used to assist the movement of bison when animal or human safety is at risk or as a last resort when all other humane alternatives (e.g., flags) have failed, and only when bison have a clear path to move. Electric prods must not be routinely carried while handling bison. Electric prods must not be used on sensitive areas such as the genitals, face, udder, or anal regions. Electric prods must not be used on calves less than 12 months of age. Willful mistreatment or intentional harm of bison must not occur. This includes, but is not limited to, beating an animal, slamming gates on animals, and dragging or pushing bison with machinery (unless to protect animal or human safety). |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- avoid using an electric prod more than once on the same animal

- initiate attempts to move animals using handler body movements only, applying knowledge of flight zones, followed by the use of further handling aids if needed (see Appendix D) (41)

- use visual handling aids such as waving devices like fibreglass rods or sticks (with flags or plastic bags attached) and panels to direct animal movement.

5.2 Facility Design

Handling can be stressful to bison (42). Bison will typically progress through a handling system smoothly and efficiently if there are no perceived threats. The goal in designing a good flow-through, passive system is to reduce as much stress and potential trauma as possible (42,43). It is best to use the minimum of everything required to process bison—including people, movement, sound, and prods.

A well-designed handling facility should create a free-flow environment where bison have a natural tendency to move easily through alleys (43). Facility designers should incorporate bison preferences to move in the direction from which they have just come and to circle when looking for escape routes (38). Footing for bison is very important in handling facilities.

REQUIREMENTSDesigns that directly and routinely contribute to animal welfare issues such as injuries or excessive stress must be corrected. Facilities must incorporate emergency access points that allow handlers to provide prompt, humane, and effective treatment or release of distressed bison. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- avoid sharp contrasts in natural or artificial lighting to minimize shadows (44)

- monitor slips and falls and take action to improve footing traction and animal safety

- use rounded corners in pens and curved alleys/races to avoid sharp corners and square or dead ends where more vulnerable animals could become trapped and injured

- intersperse circle system designs with intersections and gates to facilitate natural directional flow or movement

- use sliding versus swinging gates where possible to reduce the likelihood of trapping animals. Swinging gates are a hazard (42)

- ensure that there is a sufficient number of gates within facilities to slow the animals and prevent bison from running through long alleys and colliding heavily with gates (38)

- ensure that facilities enable handlers to operate gates without having to be among the bison.

5.3 Handling Facilities

It is essential that bison producers have access to adequate handling systems whenever they are required to collect, segregate, test/treat, load/unload, or confine animals (43).

Adequate facilities (combined with a good design) will reduce the chance of injury to animals and producers and will allow animals to move through as easily as possible. This will reduce handling time and animal stress (43).

REQUIREMENTSDesigns that directly and routinely contribute to animal welfare issues, such as injuries or excessive stress, must be corrected. All facilities must be structurally safe for animals. Facilities must allow handlers to provide prompt, humane, and effective treatment to distressed bison. Handling facilities must be designed so that animals can be fed and watered if held for more than 24 hours. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- use materials in handling facilities that will minimize potential injuries to bison (45)

- turn all connecting pins used in portable panels to the side of least pressure (46)

- move overhead ropes, electrical cables, or hydraulic cables so that bison cannot catch and drag forward (46).

5.4 Restraining

Bison are flight animals with a large flight zone. They are extremely fast, agile, and have dangerous horns. They require specialized handling equipment to avoid injuries. It is essential that restraint and handling equipment be safe for bison and handlers. Bison can be harmed if equipment is not properly designed or installed or if proper handling techniques are not implemented. Commercial chute manufacturers have increasingly made necessary improvements to ensure that processing is as safe, effective, and injury-free as possible. With bison only being handled on average once yearly, training or habituating bison to the stress of restraint is not a viable option.

Bison squeeze chutes have specific features designed to accommodate bison conformation and behaviour: a solid top with a crash gate positioned in front to stop an advancing bison before the neck restraint is applied. The crash gate is then opened allowing for access to the bison's head.

A bison squeeze has a straight and vertical neck restraint when closed. A curved restraint could block- off (occlude) the carotid arteries and cause death to a bison if it were to go down in the squeeze (38).

A bison squeeze should be designed so that bison cannot get legs or horns caught in any openings. It should also feature neck access doors for injections, a bottom access door for semen collection and foot treatment, rear access doors for palpation of cows, adjustable width sides to accommodate different sized animals, and a side animal exit(38).

REQUIREMENTSA squeeze with a head gate and crash gate capable of handling and safely restraining bison must be available. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- minimize the amount of time that a bison is restrained in a squeeze

- rope bison around the horns if required, as roping around the neck may cause choking

- drape a blindfold over the eyes to calm an animal if necessary

- avoid the use of nose tongs

- behave in a way that minimizes fear in closely held or restrained bison, as restraint is extremely stressful.

5.5 Operations

The goal in using efficient flow-through, passive systems is to be patient and to apply knowledge of bison behaviour in order to minimize animal stress throughout.

The following practices and principles will aid in the successful operation of low-stress, flow-through facilities.

REQUIREMENTSA walk-through inspection of the handling system must be performed and any necessary repairs or corrective actions taken before processing. Minor design faults must be identified and corrected. Obvious distractions must be removed. Fences, pens, alleys, walls, gates, and latches must be free of sharp edges and protrusions in order to prevent injury to personnel and animals (38). |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- identify and eliminate spaces under tub walls and between fences, panel sections and alleys where legs or horns may be caught (38)

- assess whether the spaces between any open-rail gates might allow calves to push their heads through, and correct any hazards

- check gates to ensure that all are operating properly and that those in heavy use areas are covered

- look for areas that may cause potential slipping problems and make provisions (especially if ice is present)

- consider whether any feed bunks along fences might allow or encourage bison to climb out.

5.6 Handling Considerations

Before processing or weaning, it is customary to bring a herd into a smaller area. When doing so, it is essential to try to minimize stress, fighting, and the risk of injury.

REQUIREMENTSEveryone involved in the handling operation must be familiar with the facility being used and the handling procedure. As bison are brought into tighter confines, ample space must be provided for all animals to move freely and be able to avoid more aggressive pen mates. A sufficient number of pens and pen space must be provided to separate aggressive individuals from the group if necessary. Bison must not be left in confined spaces any longer than it takes to complete the handling procedure. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- review handling practices with personnel on a yearly basis

- ensure that handlers have handling plans, personnel, equipment, and supplies in place so that animals are not held any longer than necessary

- work bison in groups to minimize stress on individuals

- instruct personnel to move slowly without making excessive noise (e.g., no yelling or slamming gates to frighten or move bison) (40)

- avoid handling very young calves during calving season

- reduce herds into smaller groups as soon as they enter the crowding alley to avoid aggression and injuries (43)

- avoid leaving individual animals alone for long periods, with the exception of mature bulls (44)

- give bison sufficient time to find an open gate before they are pressured. Do not apply pressure if they are moving well

- ensure that flighty animals are not forced in any way

- ensure that handlers develop techniques to reduce the speed of bison as they flow through the facility

- step back or retreat if animals are moving too fast or become overly excited.

5.7 Behavioural Signs of Stressed Bison

It is essential that handlers learn to recognize behavioural cues from bison that indicate they are becoming fearful, threatened, or aggressive.

Subtle behavioural cues include licking, blinking, huddling, milling (circular movement), and balking (44). As fear levels increase, these behaviours will increase, and new behaviours may emerge such as bulging eyes, running, pushing, goring, sitting, and lying down. Bison may also attempt to jump or climb out of facilities, possibly causing self-injury or injury to other bison (40). Some animals may be highly reactive when handled or directed in any way. These are the first animals that start panting. Once open mouth panting is observed, corrective action should be promptly taken.

Potential aggression may be indicated by head shaking towards a perceived threat and pawing the ground. The tail is also a good barometer of aggression; as the stress level elevates the tail will rise too—along with the potential for aggressive behaviour. A combination of aggressive signs usually precedes a charge (47).

REQUIREMENTSAnimal handlers must be familiar with normal bison behaviour and be able to recognize signs of stress. If bison being handled or directed in any way routinely exhibit severe stress or experience falls or collisions, or suffer apparent injuries, adjustments must be made to prevent recurrences. Holding or working time must be minimized when dealing with animals that are highly reactive. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- monitor bison being handled or directed in any way for signs (or sounds) of panting. If observed, efforts should be made to process panting animals as soon as possible. Otherwise they should be released.

5.8 Dehorning

Management practices, handling techniques, and commercial handling facilities and systems have all improved in recent years. As a result, it is generally recognized that dehorning non-breeding animals (feeders) is no longer necessary. Hence, dehorning is a declining practice. Under some management scenarios, there is an animal welfare benefit to dehorning breeding females to reduce goring. The individual animal welfare costs of dehorning must be balanced with the herd-level animal welfare benefits of the practice.

Loss of an external horn cuticle (horn cap) occasionally occurs during handling and does not require treatment.

REQUIREMENTSWhen partial or full dehorning results in bleeding, pain control must be used in consultation with a veterinarian. Dehorning must only be performed by competent personnel using proper, well-maintained tools and accepted techniques. Non-breeding bison must not be dehorned. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- note that dehorning replacement breeding females entering an existing dehorned herd is acceptable

- avoid dehorning males (except in the case of retained orphan calves; see Appendix F)

- dehorn during seasons where potential infection by insects is minimized (late fall-winter), and monitor dehorned animals for infection following the procedure

- note that removal of a horn (not cap) that is broken or damaged may avoid prolonged suffering or prevent further injury.

5.9 Tipping

Tipping is a non-painful and bloodless modification of the horns to create bluntness. Mature, aggressive bison can injure others with their horns. In most cases, tipping the horns—as opposed to total removal—may offset this problem.

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- tip bison horns only if necessary and on bison no less than 36 months of age. Horn modification before that age is considered partial dehorning

- limit tipping to the removal of dead horn tissue only and not the bone core inside of the horn that remains vascularized and innervated (i.e., contains blood vessels and nerves) (48).

5.10 Branding

REQUIREMENTSBison must not be branded for herd identification purposes. If branding is required for export, it must be performed with proper equipment, restraint, and by personnel with training or a sufficient combination of knowledge and experience to minimize pain. |

5.11 Castration

Bison are rarely castrated (with the exception of orphans or due to injury). Bison castration is a technically more difficult procedure than castration performed on beef calves. Orphaned bulls (see Appendix F) raised by humans can become unusually dangerous during the breeding season. As such, it is recommended that they be castrated to reduce aggression.

REQUIREMENTSBison must not be castrated unless performed by a licensed veterinarian using anaesthesia and analgesia. |

Section 6 Transportation

Desired Outcome: To prepare bison so they experience minimal stress during the transportation process and arrive at their destination in good health and condition.

Transporting bison is potentially the single most stressful event they will experience. As such, each person involved in various stages of bison transportation in Canada has a role in ensuring that the transportation process (including loading, transport, and unloading) does not cause suffering, injury or death of the animals.

If you are responsible for transporting, arranging, or causing bison to be transported, you must follow the most current national and provincial animal transport requirements (50,51). The federal requirements for animal transport are covered under the Health of Animals Regulations, Part XII (51). They are enforced by the CFIA with the assistance of other federal, provincial, and territorial authorities. Some provinces also have additional regulations related to animal transport. If you do not comply with the regulations, you could be fined or prosecuted. If your actions or neglect are considered animal abuse, you could also be charged and convicted under the Criminal Code of Canada and/or provincial regulations.

The scope of this Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Bison ends at the farm gate, but includes requirements and considerations that affect the transportation process. To avoid duplication, the Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals: Transportation (52), or the most current version of that Code, should be used as a reference document for the actual transportation process.

6.1 Pre-Transport Decision Making and Preparation

Advance planning is a key factor affecting the welfare of animals during transport. Those responsible for arranging transportation need to know how long the bison will be expected to be in transit, including intermediate stops such as auction markets, and whether the transporter needs to provide additional services (e.g., feed, water, rest) during transit.

It is the responsibility of the party that is loading (or causing to be loaded) the bison to ensure that all animals are fit for the intended journey. Fit bison are those in good physical condition and health that are expected to reach their destination in the same condition. Non-fit animals are considered to be either “unfit” or “compromised” (see Appendix G). These terms are not interchangeable.

Bison that are unfit may not be transported under any conditions, unless for veterinary diagnosis and treatment as long as special provisions1 for transport are met. Animals unlikely to recover are to be

humanely euthanized on farm. Refer to Appendix G to determine if an animal is unfit for transport.